As I write this post the COVID-19 pandemic continues to rise in the United States and Europe. At the same time colleges and universities are winding down 2020’s educational activities.

I’d like to share several updates.

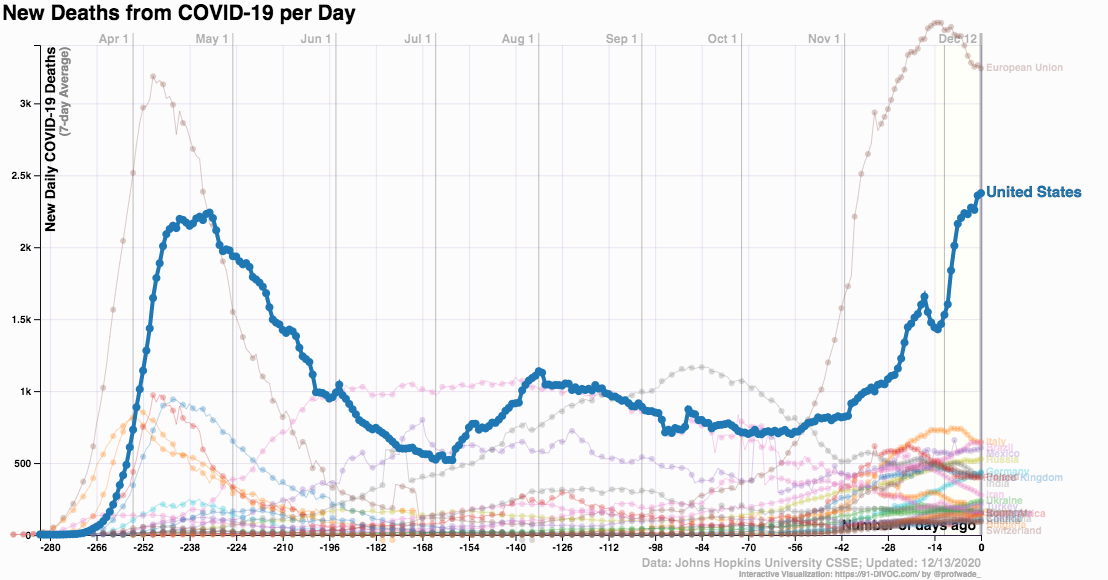

First, on the pandemic: worldwide, there are 70,461,926 confirmed cases of COVID-19. Among them there now stand 1,599,704 deaths, according to WHO. The Financial Times sees Europe as a whole leading the world in deaths:

IHME projects over 1.8 million dead worldwide by January 1.

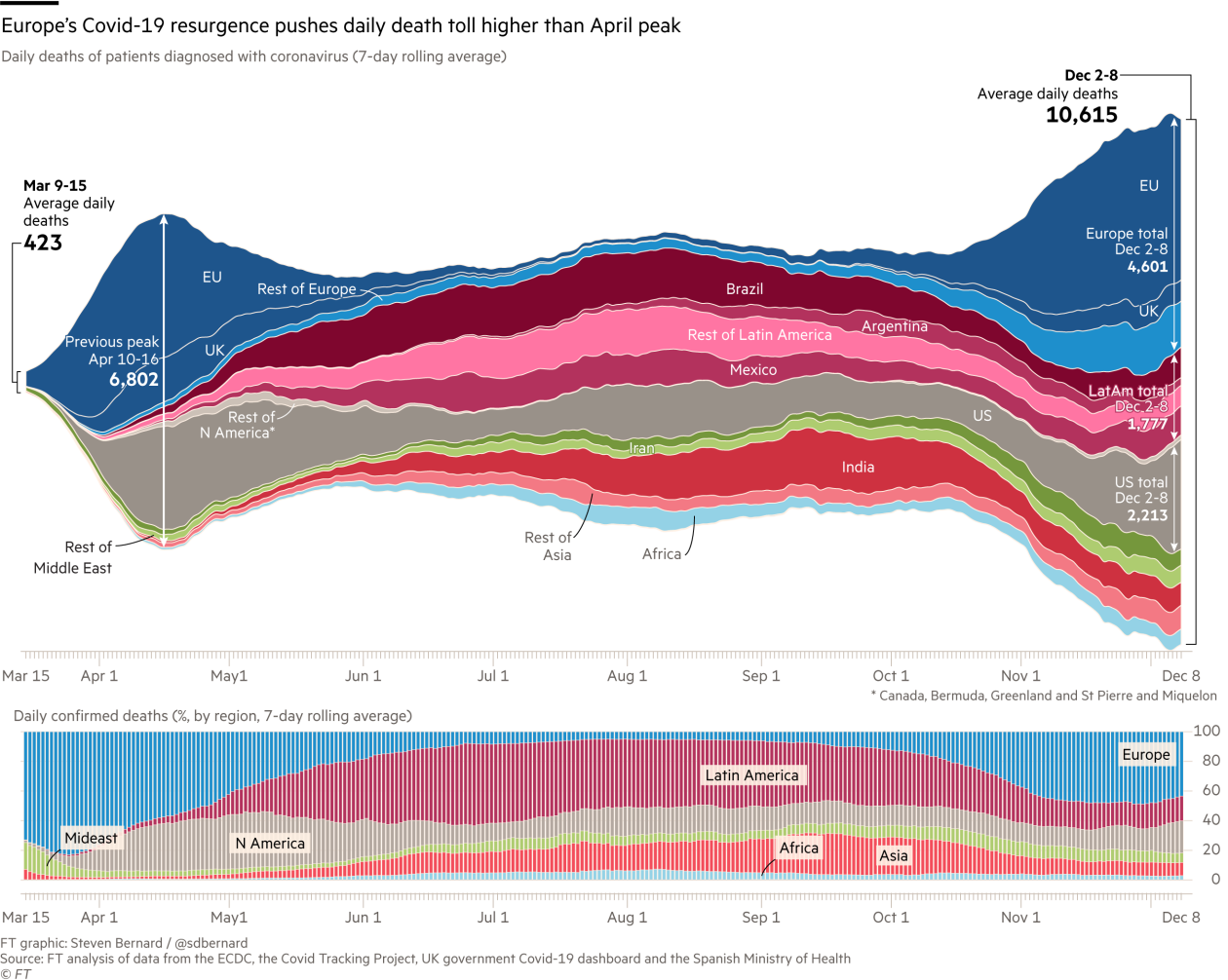

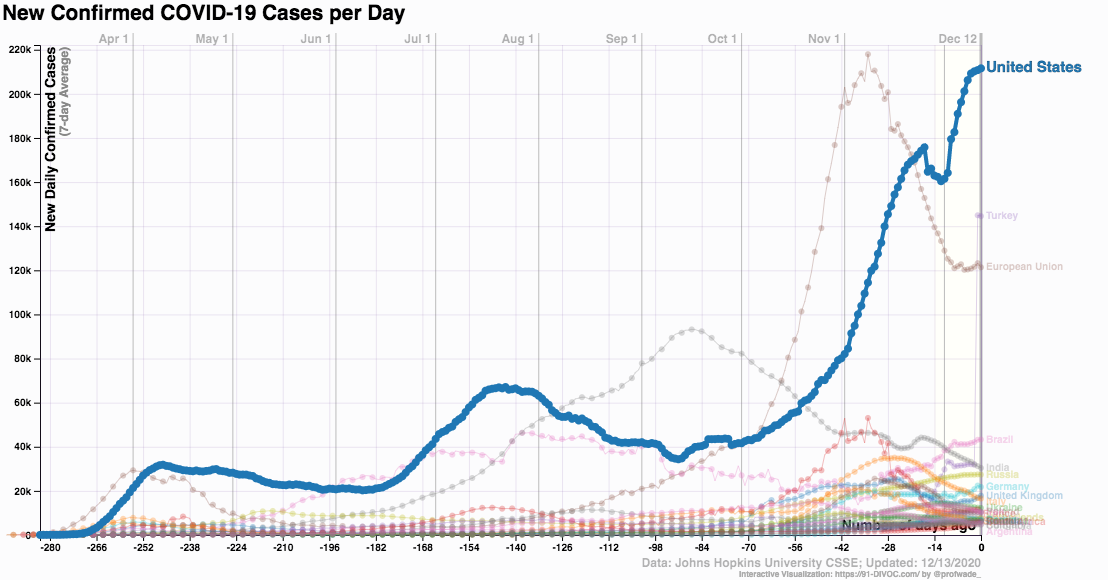

In the United States 15,932,116 people have been infected, or roughly 4.5% of the entire population. The virus has killed 296,818 people in America, according to the CDC. That number will probably break 300,000 by the time you read this. America has more infections and deaths than any other nation on earth, according to Johns Hopkins and visualized by 91-DIVOC:

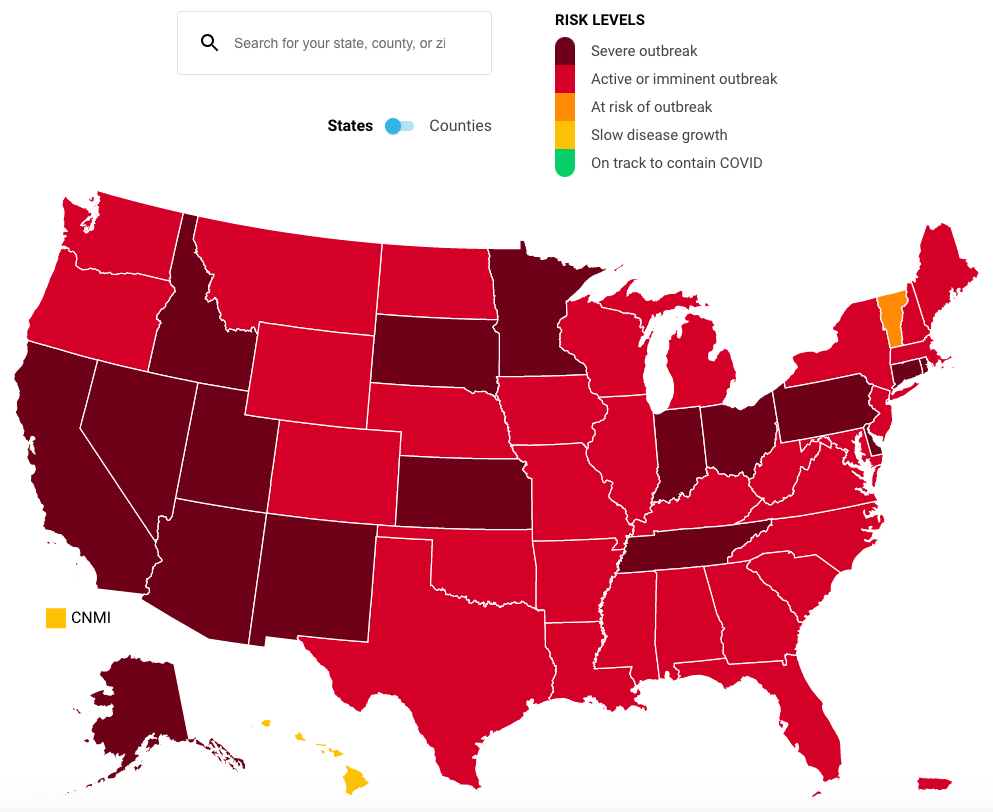

Cases are rising everywhere in the United States, in every state, according to COVID Act Now:

Cases are rising everywhere in the United States, in every state, according to COVID Act Now:

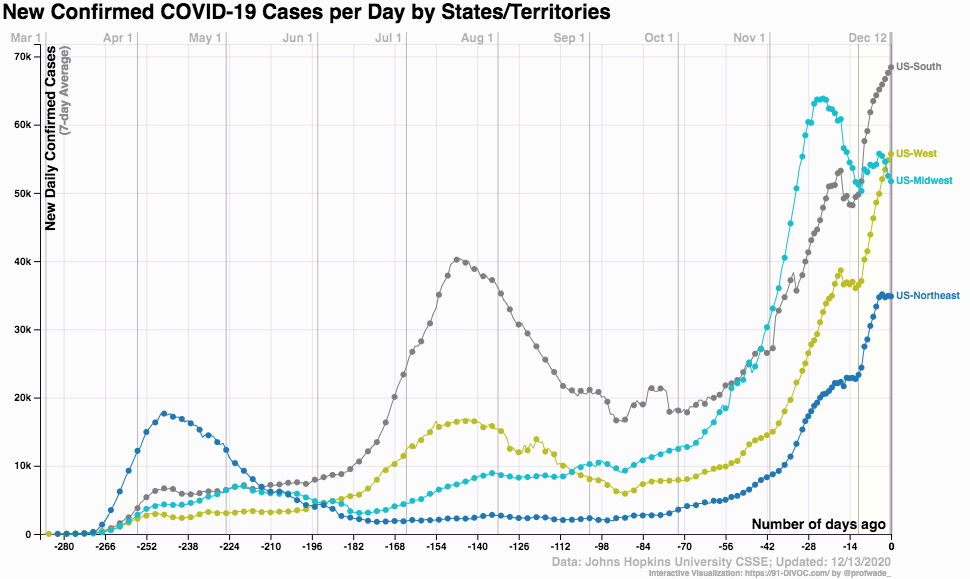

The same trend occurs broken down by regions, although the midwest seems to have turned a corner:

Looking forward, IHME projects 334,000 dead in the United States by January 1.

Against this, the first vaccine distribution commenced, starting in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

That is the pandemic context for our considerations of higher education.

(The preceding may look cold. I wrote in a mixture of fury, dread, and exhaustion. I listened to my family today, both in my house and elsewhere, and feared for every one of them. My son is living with us, taking university classes online, because he fears the on-campus infection risk. My wife is working as a contact tracer. The pandemic reaches throughout my life.)

(I don’t write about these feelings very often. I feel I can do a better service by sharing research and analysis.)

Second, a New York Times team found that colleges and universities are present in some counties where COVID-19 cases rose to unusually high levels.

As coronavirus deaths soar across the country, deaths in communities that are home to colleges have risen faster than the rest of the nation, a New York Times analysis of 203 counties where students compose at least 10 percent of the population has found…

[S]ince the end of August, deaths from the coronavirus have doubled in counties with a large college population, compared with a 58 percent increase in the rest of the nation.

Who died among the infected? “Few of the victims were college students, but rather older people and others living and working in the community.”

Is this causation or mere correlation? Did in-person education this fall infect and kill community members? In favor of causation we can identity various transmission routes. A typical one involved socialization outside of classes:

“The students came back anyway, and swooped down on bars and restaurants and other places and caused outbreaks in the community,” said Debra Furr-Holden, a Michigan State epidemiologist and associate dean for public health integration.

The Times notes an underappreciated infection pathway:

More than 1.1 million undergraduates work in health-related occupations, census data shows, including more than 700,000 that serve as nurses, medical assistants and health care aides in their communities.

And still another:

At Valley Senior Living [North Dakota], the main nursing home and assisted-living provider in town, college students make up about a quarter of employees. They help residents brush their teeth, serve meals of meatballs and potatoes and become like substitute grandchildren to people whose isolation has intensified during the pandemic.

Note that these involves students as workers. This role rarely wins media attention, but is certainly very important, especially for poor students.

Note, too, that this is partial data, only reaching a few hundred counties.

How will this impact college and university plans? Does this data play a role in delaying spring term opening? Will it encourage some to move instruction entirely online, or to at least de-densify their campus?

Speaking of partial data, the New York Times also published a frustrating report on infections within college sports teams.

It’s multiply frustrating, starting with its main finding:

At least 6,629 people who play and work in athletic departments that compete in college football’s premier leagues have contracted the virus, according to a New York Times analysis. The vast majority of those infections have been reported since Aug. 15, as players, coaches and the staff around them prepared for and navigated the fall semester, including football season.

That’s a lot of infections. I wonder how many infections they led to. How many deaths?

The Times adds that these results “collectively demonstrate how the virus can intrude on programs even when they have stringent safety protocols, including widespread testing.”

But what’s also frustrating is that this data was very hard to get, and only represents a fraction of the story. Listen to Blinder, Higgins, and Guggenheim:

The actual tally of cases is assuredly far larger than what is shown by The Times’s count, the most comprehensive public measure of the virus in college sports. The Times was able to gather complete data for just 78 of the 130 universities in the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s Football Bowl Subdivision, the top level of college football.

And “[s]ome of those schools released the pandemic statistics only in response to requests filed under public records laws.” Straight up, around half of American college football teams – and their host institutions – simply refuse to share this information with the world.

The remaining schools, many of them public institutions, released no statistics or limited information about their athletic departments, or they stopped providing data just ahead of football season. [emphases added]

The N.C.A.A. does not track coronavirus cases…

What does this mean? “This had the effect of drawing a curtain of secrecy around college sports during the gravest public health crisis in the United States in a century.” And “university leaders have routinely hidden their deliberations and debates from public view.”

Some of this academic secrecy was the result of mid-stream changes:

The University of North Carolina had reported 37 infections [in July 2020], for instance, and Western Kentucky University said it had just six.

But those schools were among the 13 that stopped releasing statistics about cases within their athletic programs. Some schools changed their approaches as the start of football season neared, abruptly citing privacy laws to justify withholding the very data they had provided for weeks or months. A handful offered no explanation at all.

As I’ve previously written, American higher education is now operating during the pandemic in a data void of its own creation. Internally, while some campuses publish some data, many do not. This drives external entities, like the New York Times, to not just conducting lots of data gathering and analysis but also investigation into what actually is occurring, and at an enormous scale, with hundreds or thousands of institutions. And the Times, despite its excellence and resources, still can’t get data on even one half of American higher education.

We don’t know how many infections there are among college and university populations. We don’t know how many deaths have resulted. In far too many cases, and certainly in the sector as a whole, we can’t meaningfully judge pandemic responses.

This data void impacts everyone in or adjacent to the academic enterprise. Students, librarians, faculty members, presidents, other staff of all kinds, family members; funders, state governments, publishers, communities abutting campuses: we are all forced to make decisions with a damnable paucity of information.

We can, and should, do much better.

Let us not completely forget the other epidemic cutting down Youth in the USA.

Drug overdoses are up almost 18% over last year.

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

http://www.odmap.org/Content/docs/news/2020/ODMAP-Report-June-2020.pdf