Today one of my classes is going to be the first to play an educational game I’ve been working on. It’s an experiment, and I’m very excited to see how it goes.

The class is my future of higher education seminar in Georgetown’s Learning, Design, and Technology graduate program. (Here’s a description of last year’s instance.) Students have been reading, thinking, and writing about how colleges and universities work, how they change, present day trends shaping them, and numerous future scenarios for where they might go. Several took my summer gaming in education seminar, so they should be ready to share thoughts from that experience.

The game they’ll play is called Future University, and it’s a matrix game. These are unusual hybrids of role-playing and tabletop games, where players have a great deal of freedom to act and rules are relatively minimal. A key feature is that play largely consists of player describing actions they would like to undertake, followed by a supporting argument, then all players hashing out the likelihood of the thing actually occurring.

A facilitator or referees adjudicate each action, at times setting up a resolution structure, and recording the resulting changes on a shared game map. All of these action attempts and their outcomes build up into a collaborative narrative. Historically, matrix games emerged out of the wargaming and defense worlds originally, but are open for general use. (For more background, try this or this.)

Why would anyone use this framework for a game? Partly it’s to free up player imaginations by avoiding elaborate rules. It’s also designed for mental exploration. I like Paul Vebber’s description:

Rather than explore what happens when we are told: “here is a set of tools, go solve this problem”, Matrix Games provide a means to “explore what problems there might be, how to characterize them, and how to devise a set of tools that you think might solve them.” *

Furthermore, I’ve been working on a solitaire tabletop version of this game for months – and it’ll appear eventually. Here I wanted to emphasis the social aspect of gaming, which is important for the topic as well as for the pandemic.

How Future University works:

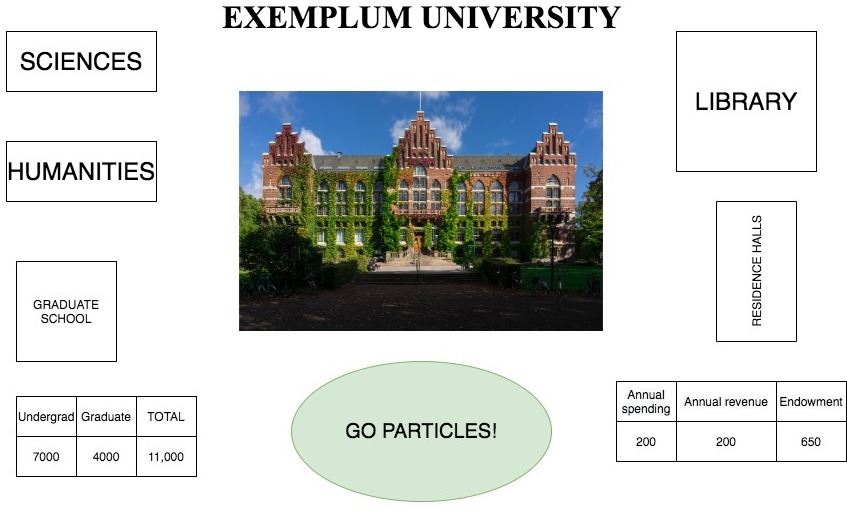

I’ve created a hypothetical campus, Exemplum University. It’s a research-2 institution located vaguely in the mid-Atlantic area. Students will receive a short briefing sketching out its history and present-day details. They also receive a very short rulebook.

Students then volunteer/are assigned to play various roles at Exemplum. They include:

- University president

- Provost

- Chair of board of trustees

- Humanities faculty members

- Science faculty members

- Head of student athletics

- Non-faculty staff, including the VP for information services (IT + library)

- Students, including both undergraduates and graduates

We have ten students in the seminar, so some will pair up on roles, while others represent individually. Each receives a very short description of their character or group’s background, interests, and challenges, along with some notes about campus relationships.

Each game turn represents one full academic year, starting in autumn and ending the next calendar year’s summer. On each turn we take the following steps:

- Update on university status

- Player Actions stated and resolved

- Update on university and world events. Random events will pop up here.

They can all see the game board, which looks like this:

Remember, this is a draft! Very DIY. No professional designers were involved or harmed in the making of this board.

Here’s a sample action and resolution:

For their Action, the provost team announces they will attempt to launch a new center for interdisciplinary studies. For their Argument, the provost describes having won financial commitments from the trustees and interested professors from the faculty. Their goal is to produce spectacular research and attract more students.

Other players weigh in. The athletics player thinks this might lead to cost overruns if there’s a new building involved. The trustees confirm their support. Students think this could be attractive. The humanities player argues that this should help build up a better sense of campus community, while the scientists respond that this will fail due to a lack of that community. The president remains silent.

The facilitators rule that there is no consensus and set up a dice roll. They assign +1 for the trustees’ monetary support and -1 for faculty dissensus. The roll comes up 9 and remains so as the modifiers cancel out. Facilitators congratulate the provost on their success, but warn them that a cost overrun is a possibility on the following turn. They add a Center for Interdisciplinary Studies marker to the campus map.

How will we make this work, in practical terms?

My current plan is to introduce the game in today’s class. Students will pick up roles and receive documents. I’ll talk them through the ideas and give them a chance for basic questions. This will also give me a sense of how to facilitate play.

Over the next week they’ll play an asynchronous, first turn on in our discussion forum (in the Canvas learning management system). They’ll issue actions by early next week, then respond to each other’s proposed actions with supporting or opposing arguments. I’ll adjudicate it all and share results online, including an updated game board. Throughout the week they’ll have plenty of chances to work with each other, comparing notes, planning actions, scheming, etc. They can also ask questions about the game’s world, which we’ll flesh out together.

Then in next Thursday’s class we’ll go further, playing three turns on live video (Zoom). Depending on how this goes, we’ll attempt another asynchronous turn over the following week. The next Thursday is a debrief, where we compare reactions to what we learned.

Assessment: I’m considering playing Future University to be a week of class discussion. That means I can check on how students are applying their learning through play, both during asynchronous writing and synchronous sessions.

Since this game offering is an experiment, I have some latitude in how it’ll unfold. For example, I’ve produced some game turn worksheets, which I might or might not use. I’m still thinking about how to show actions on the map – what kind of counters to add, or changes to the displayed data. (If we were in person, I’d bring a box of counters and wouldn’t alter the printed board. I might have to add tracks for metrics, too.) I’ll have to figure out how much world building I need to add, and how much players should contribute. They’ll also have a lot of room to explore.

Where this goes next: it depends on how play transpires. There should be a hefty amount of playtest feedback to hurl me back to the drawing board. I’ll revise the design on multiple levels. Then… offer it for next year’s class, maybe. I could also offer it for other groups or settings. I can also set up different scenarios, such as for a liberal arts or community college. Eventually I’ll have to put a bow on it and see it into the world, perhaps as an ebook.

What do you think? Any recommendations, howls of outrage, thoughts of intrigue?

(Thanks to many folks for feedback, including Todd Bryant, Michael Haggans, Tom Haymes, Ruben Puentedura, Vanessa Vaile, and Justin Vasselli. Special thanks to Stephen Aguilar-Millan and the summer 2020 Dragon, Bear, Steppe game players. Thanks, too, to the LDT program for hosting my mad experiments. Lund University building photo by barnyz. Exemplum exemplum photo from Yale Law Library.)

*In Curry, John, ed. The Matrix Games Handbook: Professional Applications from Education to Analysis and Wargaming, p. 221.

So instead of Model UN, it’s Model Uni?

Sounds intriguing!

Steve, I may actually borrow that perfect pun.

Alas, we in the states don’t use the “uni” form very often. It’s either “university” or “U.”

Steve Foerster beat me to it, but I was going in the same direction wrt Model UN. I think you are missing roles for the CFO and the Dean of Students. As a university simulation, you probably need at least one professional school dean. The Med School is probably the most useful as a complicating factor (different academic calendar usually, and multiple allegiances with hospital at play).

Those are really good suggestions, Anthony.

CFO/CBO can take over the financial questions from the facilitator.

Separating out the med school can head in a few different directions.

Have you considered assigning “motivation” points to players so that if certain outcomes transpire they run up a positive score? I did this with the Congress simulation I shared with you.

Hm. I wonder what kinds of motivation points would work. Reputation?

The beauty of the system is that it doesn’t matter. You can have some actors motivated by reputation, some by financial gain, and some by whatever you like. Points are points. The objective is amassing points (and avoiding deductions). As the game master you need to figure out the kinds of things that would motivate that particular actor. You can introduce whatever plot points you like to justify it (or leave that for the player to decide). I often got questions in my Congress simulation of, “why would my player want to do that?” and I used those as teaching moments and asked the students to speculate on what might motivate a particular player to torpedo legislation, for instance. I can game out a bunch of options that might motivate a college leadership team both altruistic and self-serving in nature. Is the Faculty Senate president representing the needs of the faculty or is she angling for an administration position? With this system you can fine tune a lot of outcomes (and change them up fairly easily in future iterations). The interaction of the actual personalities of players with motivation points generated all sorts of unexpected outcomes.

Good point.

It would help to have something everyone can use. I mentioned reputation up above, and making it central would actually be teachable.

FYI on gamification of CPA CPEs.

https://www.journalofaccountancy.com/podcast/value-of-gamifying-cpe-learning.html

How is this similar? different? Thanks! Glen

Similar. We’re both drawing from the same intellectual tradition and practice (did you see my posts about the gaming seminar I ran this summer?).

We’re also both offering a learning exercise structured as a game.

There are some differences, based on what I heard and inferred from that podcast. Kelly Richmond Pope’s investigation game has a clear answer at the end (detecting the guilty party), while matrix games are open ended. I don’t know how hers is structured in terms of turns, while mine has a clear sequence.