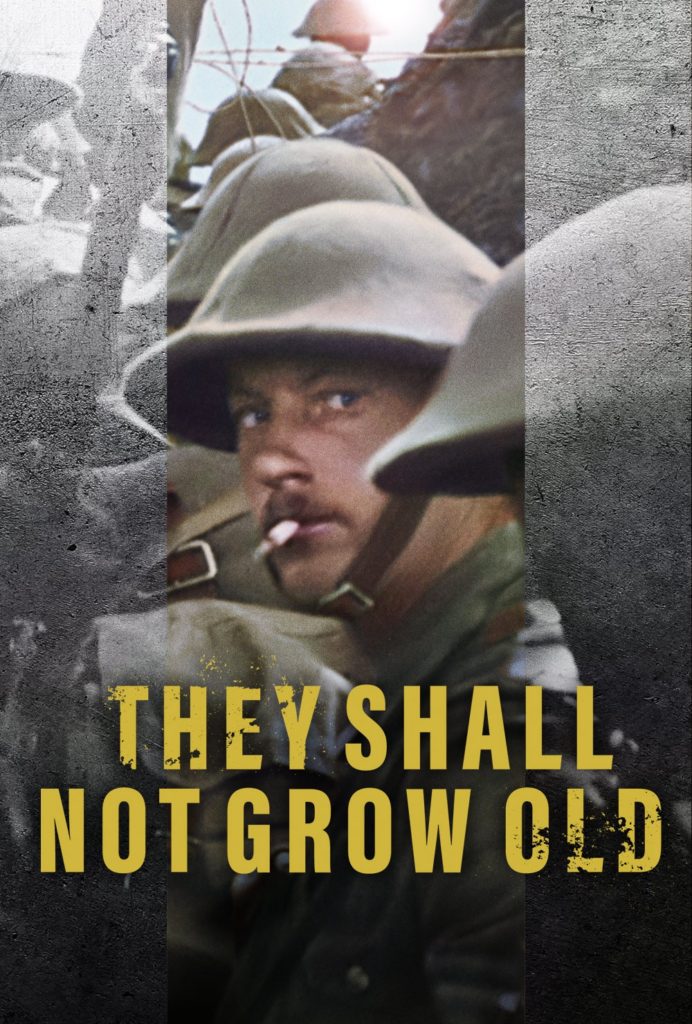

After seeing They Shall Not Grow Old I was going to recommend it for everyone. It’s received plenty of glowing reviews (97% on RottenTomatoes), so rather than piling on I’ll offer instead some reflections about what the film means for… digital storytelling.

If you haven’t heard of it, the movie is an unusual documentary about the British in the first World War. In terms of content it covers familiar historical ground: the experience of troops as they went through the war’s start, training, the trenches, battle, and victory. What’s extraordinary is a technical feat Jackson’s team pulled off.

If you haven’t heard of it, the movie is an unusual documentary about the British in the first World War. In terms of content it covers familiar historical ground: the experience of troops as they went through the war’s start, training, the trenches, battle, and victory. What’s extraordinary is a technical feat Jackson’s team pulled off.

Around fifteen minutes into the movie is when it happens. Up until then all we see is footage that feels contemporary to the first World War: jerky, silent, black and white, weirdly jittery. The image takes up half or maybe 40% of the move theater’s screen. Then, without any warning or narration, the image doubles or triples in size, widening, growing taller, gradually swelling up to fill the complete screen. At the same moment the footage’s timing seems to slow down and stabilize. The jittery action smoothes out. Also at the same time colors fade in, adding to the familiar blacks and whites strange reds, blues, browns…

It’s like that famous moment in The Wizard of Oz, when things shift from Kansas to Oz, if you first see it when you’re a child. It also gave us in the theater the uncanny feeling of having accidentally stumbled into a historical reenactment seen on YouTube, or of somehow peering straight through the veil of time itself. I thought I was seeing double, or a transmission from a parallel universe when color film was available for British film crews in the trenches… when it didn’t just feel ordinary. We quickly acclimated to the marvel. It is uncanny, I say again. I like Melissa Leon’s response: it’s “basically science fiction.”

The surreal experience is very much like seeing the stabilized Zapruder film, when you’re used to the jittery iconic footage:

Besides the stabilization, the color felt right, not like the cheesy, awful colorization inflicted on so many movies during the 1980s.* In addition Jackson’s team added splendid sound. Actors read contemporary documents (diaries, letters, newspaper articles, speeches), and a fine Foley effort added sound effects. The details became extraordinary, with not just lip synching, but people playing music from period instruments when on screen, a purchased artillery battery (!) firing for effect, and more.

(See Mekado Murphy’s article for more on this, including some fine short clips.)

Why, then, do I mention this movie in terms of digital storytelling?

First, while it took Peter Jackson’s professional team to invent this technique and make it work at professional scale, my hope it that it will gradually become available to individual creators. Perhaps we’ll have access to it as software, like Autotune, or as a plugin within another application, much like iMovie hosts the Ken Burns (animation) Effect. Imagine how individual storytellers could use this approach for older or flawed footage.

Second, there is no narration at all in They Shall Not Grow Old. None whatsoever. There are no framing devices, explanations, reflections on what we see.** All dialogue consists of either actors reading primary source accounts or veterans speaking (in the 60s and 70s, I think). Their voices are orchestrated in such a way as to make sense (see below). It’s a great example of the StoryCenter principle of “the gift of voice”: that unique presence expressed by a person’s speech. You don’t need to have access to British imperial archives and a staff of actors to do this yourself.

Third, Jackson’s team organizes all of this materials into a clear if unmarked shape. We follow a rough chronology, starting with reactions to the war’s breaking out. Then we shift to a kind of generic soldier’s experience: enlisting, training, shipping to the front, the experience of trench warfare, the experience of combat, and the war’s end.

It’s a single person’s arc applied as template across an entire generation. The approach trusts the audience to make sense of things.

Overall, it works very well, and is a fascinating lesson in how to organize disparate materials into a narrative.

Fourth, at its climax the movie shifts its visuals quite radically.

There are very few scraps of film depicting actual combat, so They Shall Not turns instead to a contemporary periodical. Images of fighting from The War Illustrated take up the screen, and the camera moves across them, giving each extra energy while the voiceovers continue.

I was surprised by this, but few reviewers have noted it, so perhaps either my focus on digital storytelling gives me extra investment in the moment, or those writers simply didn’t think it was interesting. Digital storyteller practitioners recognize this use of static images as a staple of the form. Jackson’s use here is inspired.

(By the way, the glorious Internet Archive seems to have the entire run of War Illustrated.)

Fifth, while the film has received oceans of support, there has been some pushback, and this suggests ways we should think about digital stories’ audiences and impact. Tim Carmody issued a blistering critique. of They Shall Not. I don’t have the time to address each point – I’m sympathetic with some, but think he really misunderstand’s the film’s production process – but wanted to draw attention to it as a criticism of media selection. Carmody charges Jackson for making a movie that’s far too narrow in focus, lacking any nationality other than British, any race other than white, and any gender beyond male. As we create and select media for multimedia stories, we have to listen hard to our audience’s expectations for representation.

There is much more to be said about the film, but I’ll leave it here. It’s a fine documentary, and a real stimulus for people working in digital storytelling.

(War Illustrated image from Wikipedia)

*Siskel and Ebert: “They arrest people who spray subway cars, they lock up people who attack paintings and sculptures in museums, and adding color to black and white films, even if it’s only to the tape shown on TV or sold in stores, is vandalism nonetheless” (outbound link dead, alas)

**The movie is briefly introduced by Jackson, and is followed by a “making-of featurette.” Stick around for the latter. It’s fascinating.

I’m really stunned by the short-sightedness of Carmody’s critique. Jackson addresses this in the post-film discussion. He had a lot of material, and a comprehensive documentary would skim over the surface. In the end, we’d have gotten a survey course, not a seminar.

The work Jackson did made a nearly forgotten (at least to my students) but terrible event come alive. Having lost a great grandmother to starvation during the Allied blockade of the Ottoman Empire, my family recalled the awful price civilians paid, too.

In every shot where a soldier locks eyes with the camera, a life is relived. I’ve never seen anything like it. I hope there will be more of this work with the many hours of film Jackson could not process.

Well said, Joe. I think Carmody either didn’t watch the discussion or just didn’t pay close attention.

Where was your great grandmother?