How does the high school to college pipeline look?

Many American colleges and universities recruit undergraduate students from the pool of recent high school graduates. This is usually the stereotypical first-year college student image, a bright 18-year-old who transitions from their senior high school experience to being university frosh over a short (if dramatic) summer. It’s only one segment of the higher ed student body, as more and more adults enroll, but let’s focus on it for now.

The Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE) just released an updated report on high school graduate population projections, and it’s sobering for those who haven’t been tracking this issue in particular or demographics in general.

tl;dr version: high school grads will peak in 2025, then decline.

Let’s dig into the report and bring out some highlights.

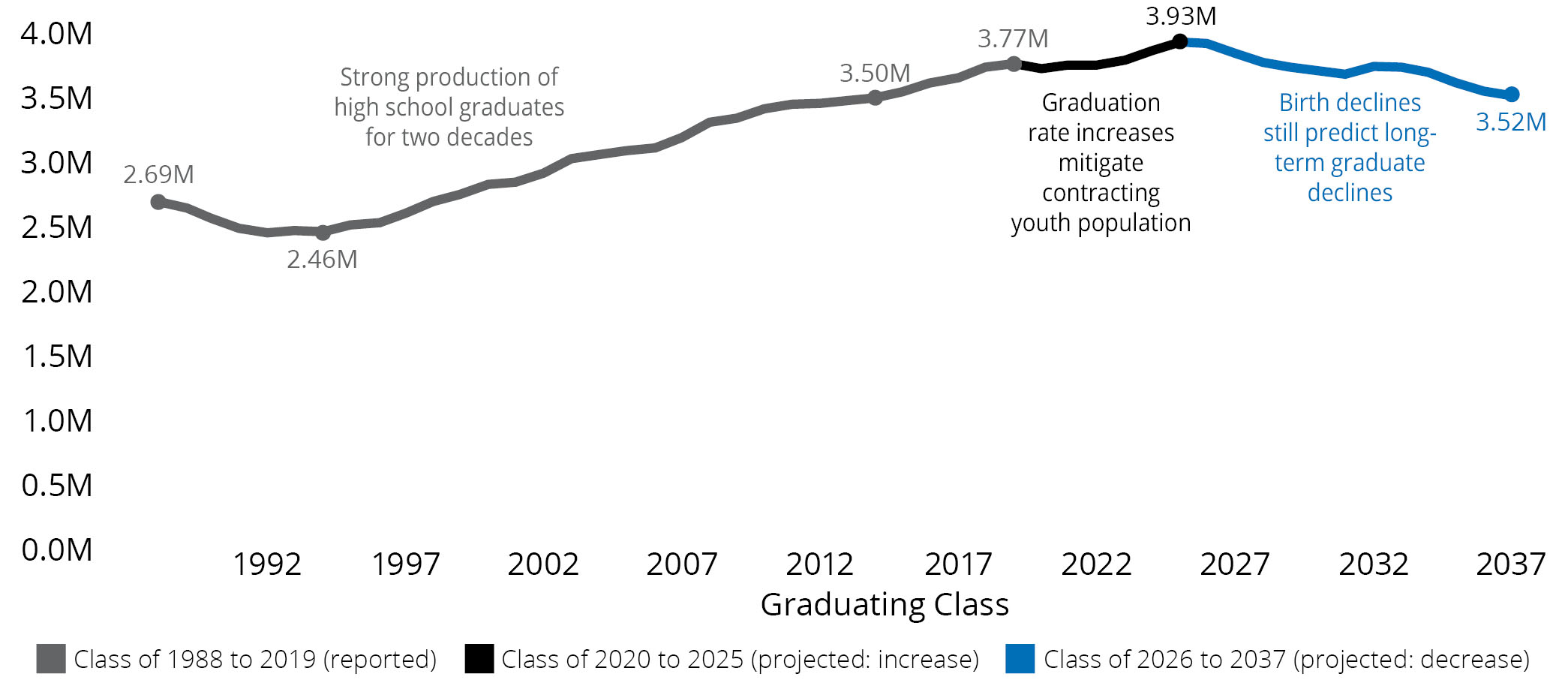

WICHE situates their projections in recent history. Consider their graph:

From the early 1990s on high school graduation numbers really soared. This helped feed into the major higher ed expansion at the same time. But starting in 2025 those numbers will start ticking down. That downward slope continues for more than a decade. “The U.S. high school graduating Class of 2037 is projected to be about the same in number as Class of 2014 (3.5 million).”

This is a national overview. Regional differences can be strong. WICHE forecasts midwestern and northeastern graduate numbers to keep falling, while the south (mostly Texas and Florida) continues to produce bigger graduating classes. In the west, it’s mostly about one state:

The number of California graduates continued to increase heading into the projections, but at about half previous rates of increase: total California high school graduates increased 2 percent annually, on average between 2003 and 2011, and 1 percent annually, on average between 2011 and 2019. Predicted stagnation in high school graduate numbers for California, and then predicted contraction…

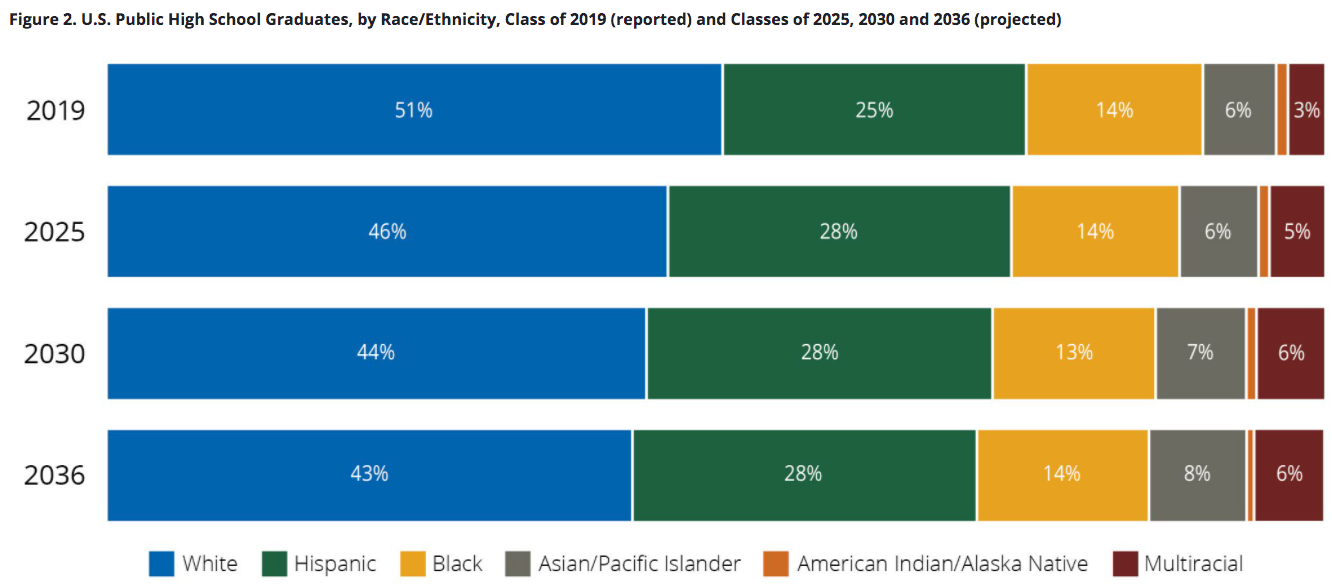

In terms of race and ethnicity, WICHE supports the consensus view: declining white numbers, unchanged black graduates, and rising Asian and multiracial populations. One surprising detail for some is that Latinx birthrates have started dropping. “[A]fter 2007, the greatest decreases in births accrued with Hispanic mothers – with 17 percent fewer Hispanic births in 2018 than 2007.”

One key point, and WICHE is careful to make this right away: the report does *not* account for COVID-19. It’s based on data extending through the year 2019. National Student Clearinghouse data indicates that 2020 saw a major drop in high school grads enrolling in higher ed. WICHE thinks that 2020 grad numbers might actually be higher, as schools tried hard to be flexible, but that 2021’s class may shrink.

What does this mean for higher education?

On the one hand, the rising numbers for the next five years may cheer admissions offices and those who pay attention to their work. Amid the many difficult short- and long-term trends, this looks like a medium-term opportunity, at least for campuses seeking to fight against enrollment decline. It helps that the actual numbers for 2019 were higher than WICHE anticipated.

On the other, the 2025 peak is right in line with Nathan Grawe’s model. Some of you will recall that Grawe forecast a drop caused by the 2008 financial crash and its negative impact on childbirth. 2008 + 18 takes us right to 2026. Inside Higher Ed quoted a WICHE leader on this:

“That good news really can’t escape demography,” said Patrick Lane, vice president of policy, analysis and research at the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education. “There are simply fewer students available that were born in and after the Great Recession to fill college seats going forward.”

The WICHE report may also encourage people in and around academia to pay more attention to demographics, because changes to birthrates are a fundamental driver behind those high school graduation numbers. And the powerful trend here is for fewer births.

Some campuses may decide to expand ties with high schools in order to improve the flow of students from the latter to the former. There are all kinds of ways to do this, of course, including letting high school students take college classes, colleges loaning advanced scientific equipment to K-12 districts that can’t afford them, and so on.

Another strategy may be to recruit more from private high schools, as they are now doing better that publics:

Nationally, private high school graduates are now projected to increase in number by as much as 13 percent from Class of 2017 to 2025… Then, even as the number of U.S. public school graduates is projected to begin contracting after 2025, 9 percent more private high school graduates are projected by Class of 2030 compared to Class of 2017. Private high school graduates are projected as 10-11 percent of U.S. total high school graduates over the course of the projections. So, while public school populations still drive the overall number and patterns for total U.S. high school graduates, these positive private school trends contribute some “cushion” to the overall downward trend that is predicted by annual decreases in the number of young children beginning with 2007.

We could also see the reverse, as some campuses cut back on recruiting 18-year-olds in favor of adults.

Another strategy: improving outreach to students of color, as they constitute a growing aggregate. Obviously this is a major concern in 2020. Perhaps the WICHE report will spur institutions to keep focusing on that in the future.