Yesterday my wife and I took another long walk. It’s become a Saturday routine for us, doing a four mile loop from our house and through the surrounding area. We mask up and rigorously maintain social distancing, quickly shunning anyone who walks, stands, or bicycles anywhere near Ceredwyn and I.

At the farthest distance from our house we visited a refurbished furniture store, checking on bookshelves, tools, and creepy kitchenware.

The shop is excellent about pandemic measures, with everyone masked up and keeping the heck away from each other. Appropriately for an establishment emphasizing repair and DIY, they built their own plexiglas shielding at the counter. This time, however, we struck out, finding nothing good.

Walking back home, we discussed where COVID-19 was headed and pondered how the election might play out (because that’s how we roll). The temperature dropped and skies tended towards gray, despite the sun’s best efforts.

We talked about higher education and what was happening to it now. I couldn’t shake the feeling that academia just took several very bad hits. Obviously these are financial and biological, as my readers know well. But I wondered, and wonder now, if in addition our reputation just dropped a notch.

I’m not thinking of any individual campus, but of higher ed as a whole.

Let’s start with the sense that some people have, that higher ed is spreading COVID-19. Not that colleges and universities started the thing, of course, but that we are making it worse. For example, the Washington Post introduced one article with this stark headline:

After a college town’s coronavirus outbreak, deaths at nursing homes mount

Can you read that in any way that isn’t awful? Try paraphrasing it: “Colleges kill old people.” Or try a milder translation: “Campuses actively threaten senior citizens.”

If you think the editor just slapped a scary headline on a gentler article to get eyeballs, read the actual story. Here’s the start:

Mayor Tim Kabat was already on edge as thousands of students returned to La Crosse, Wis., to resume classes this fall at the city’s three colleges. When he saw young people packing downtown bars and restaurants in September, crowded closely and often unmasked, the longtime mayor’s worry turned to dread.

Now, more than a month later, La Crosse has endured a devastating spike in coronavirus cases — a wildfire of infection that first appeared predominantly in the student-age population, spread throughout the community and ultimately ravaged elderly residents who had previously managed to avoid the worst of the pandemic.

Two sentences in and already we have a community figure viewing colleges with dread. Third sentence and campuses are typhoid Maries, “ravag[ing] elders.”

The article doesn’t let up. It goes on:

For most of 2020, La Crosse’s nursing homes had lost no one to covid-19. In recent weeks, the county has recorded 19 deaths, most of them in long-term care facilities. Everyone who died was over 60. Fifteen of the victims were 80 or older. The spike offers a vivid illustration of the perils of pushing a herd-immunity strategy, as infections among younger people can fuel broader community outbreaks that ultimately kill some of the most vulnerable residents.

Try paraphrasing or generalizing from that passage. Wisconsin colleges kill old people. Campuses kill grandparents. This is not, as they say, a good look.

We can go further. Linked from the article is an academic study, a preprint examining viral spread in La Crosse. From the abstract:

Genomic sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 cases in La Crosse during that period found rapid expansion of two viral substrains. Although the majority of cases were among college-age individuals, from a total of 111 genomes sequenced we identified rapid transmission of the virus into more vulnerable populations. Eight sampled genomes represented two independent transmission events into two skilled nursing facilities, resulting in two fatalities.

In other words, there’s a causal vector between college operations and off-campus seniors sickening and dying.

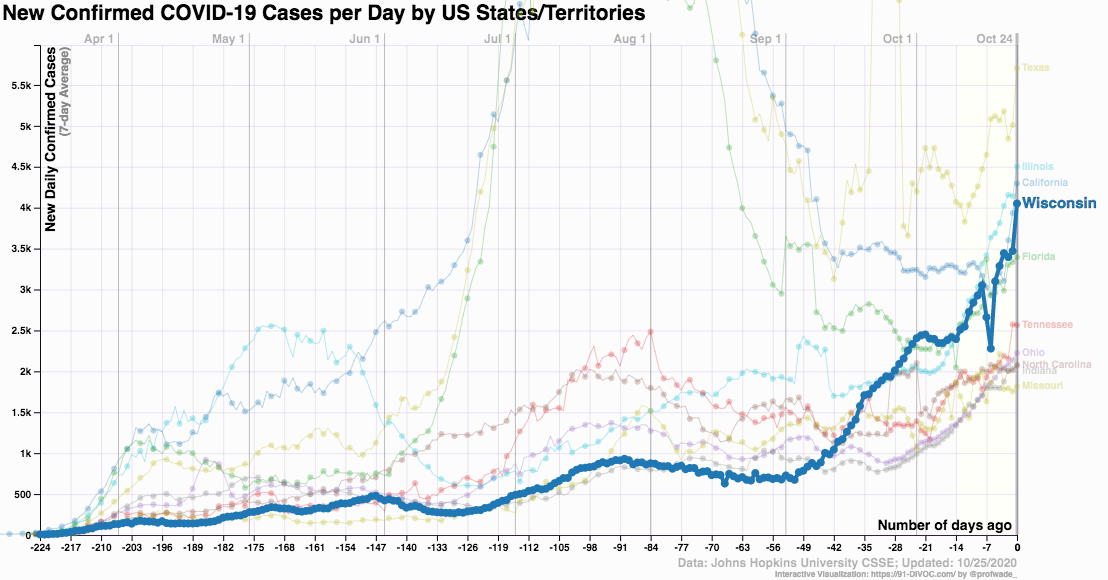

A skeptical reader at this point could observe that Wisconsin is an unusually bad case. COVID-19 is really growing there, apparently aided by a Republican legislature. Here’s today’s 91-DIVOC visualization:

Wisconsin soared even past Florida!

But other states are also seeing this pattern of rising academic infections leading to off-campus illness and death. Texas, leading the nation in infections, also has examples of town-goal virulence. In Lubbock, for example:

As football fans tailgated without masks outside Texas Tech University’s 60,000-seat stadium in West Texas this weekend ahead of the Red Raiders’ homecoming game, it was easy to forget that Lubbock — a rural county of 310,000 — has one of the highest coronavirus infection rates in the country.

The outbreak at Texas Tech, which has infected at least 2,200 students, comes as the U.S. reported a national single-day record of new infections — 83,757 — Friday. Part of what’s driving the national increase in infections has been a surge in college towns where restrictions have eased since students returned this fall. And nowhere is it more prevalent than in Texas — which has more infected college students than any other state in the country, 17,133, according to a New York Times database — and at Texas Tech itself, with more infected students than any other school statewide.

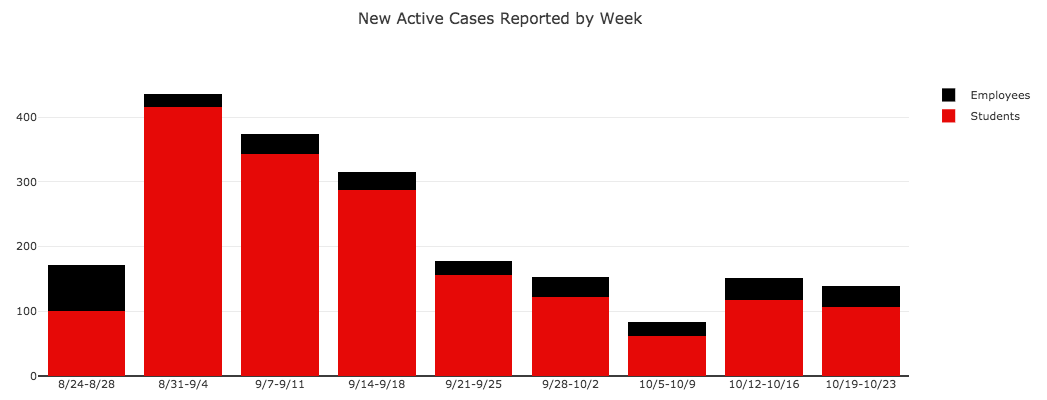

If I read the Texas Tech dashboard correctly, only 206 people at that institution are presently infected. Their trends page shows an alarming spike in August and September, with things down to a simmer now:

Yet, as the LA Times observes, “[b]ecause student testing is voluntary, the number of infections could actually be significantly higher.”

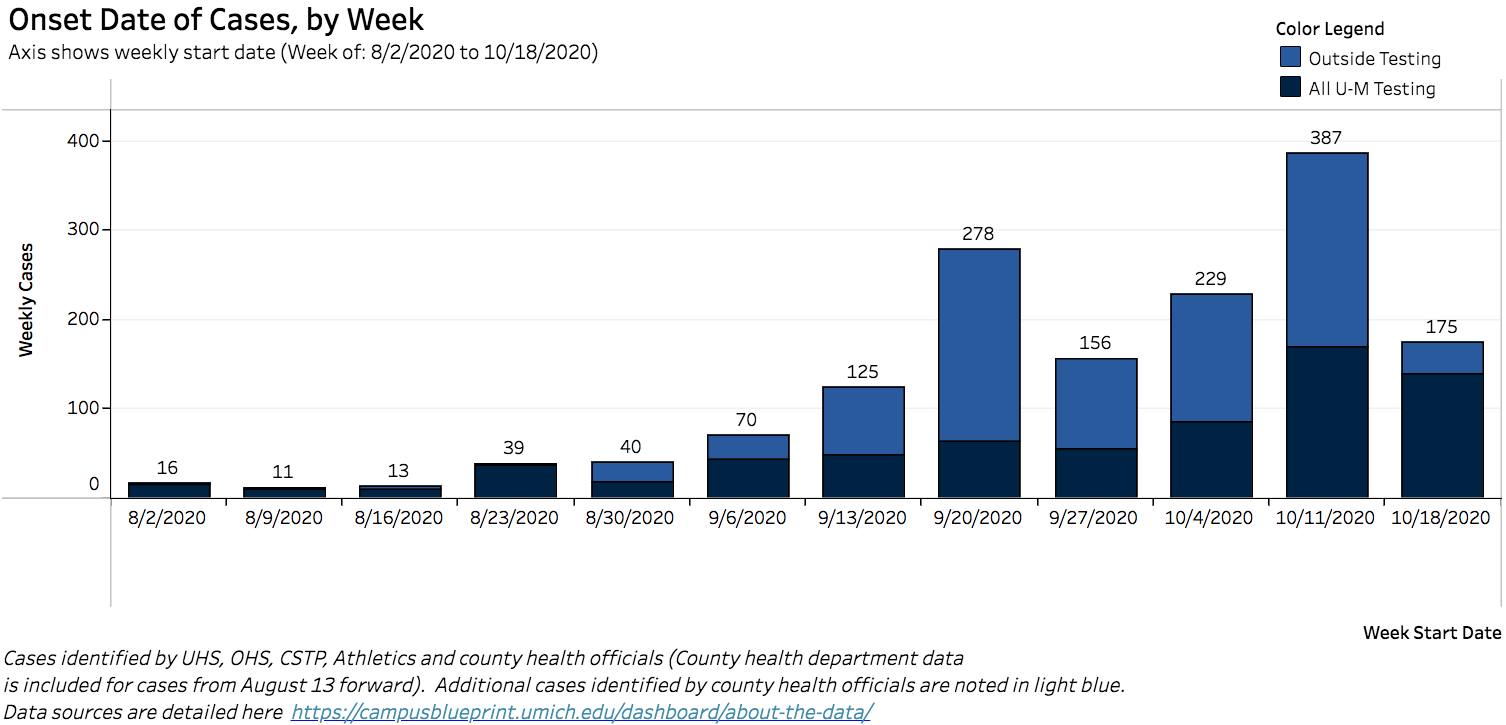

Last week I pointed to the case of the University of Michigan, whose rising infections prompted the county medical authorities – not, note, the university’s – to order undergrads to shelter in place. UM’s dashboard shows rising cases over the past few weeks, both among academics and those living in the immediate area:

We can think about this data and these events in several ways. First, campuses that welcome back students are all too often experiencing infections. Second, they can then infect – and sicken, injure, and kill – people in the surrounding areas. Third, campus leaders are willing to risk such illness, injury, and death for financial reasons: to keep their institutions going.

Surely these thoughts must make American colleges and universities look like monsters or incompetent, dangerous, bumblers.

And yet.

I’m not a marketer. I know I can have a difficult time sussing out popular attitudes (for example). So take this with a grain of salt, but there are some ways Americans might look more favorably upon our COVID-spreading campuses.

Our love of college sports Some broad tranche of American culture deeply loves our athletics, football and basketball in particular. Football obviously causes a spectacular range of injuries in its normal course of operations, but we accept them as part of the game. Perhaps this population will similarly accept coronavirus spread as a necessary cost of doing a much valued business.

Our love of the physical campus and disdain for online schooling The physical college or university environment holds a special place in our national consciousness. It hosts a residential experience for some, which we clearly value very highly (cf Ian Bogost’s recent column). Apparently that valuation is high enough that we’ll pay a special fee this year. Back to the LA Times piece:

Joyce Zachman, executive director of the nonprofit Texas Tech Parents Assn., said she hears more concern from parents about students being forced to take classes online than about them catching COVID-19.

“It’s not the college experience that parents had hoped for their kids,” said Zachman, who’s asthmatic but still attended Saturday’s game, where fans sang the school fight song with its chorus of “Wreck ’Em!” and pointed their trigger fingers in the Texas Tech “guns up” victory sign.

Did you catch that first bit? Zachman is more worried that students will take classes online than that they might catch COVID-19. While some of us might find this an astonishing view, it is, apparently, a view held by enough people to matter.

COVID-19 is less dangerous than it was I have heard from some conservative friends and commentators that while coronavirus infections might be rising, hospitalizations and deaths are not following suit.

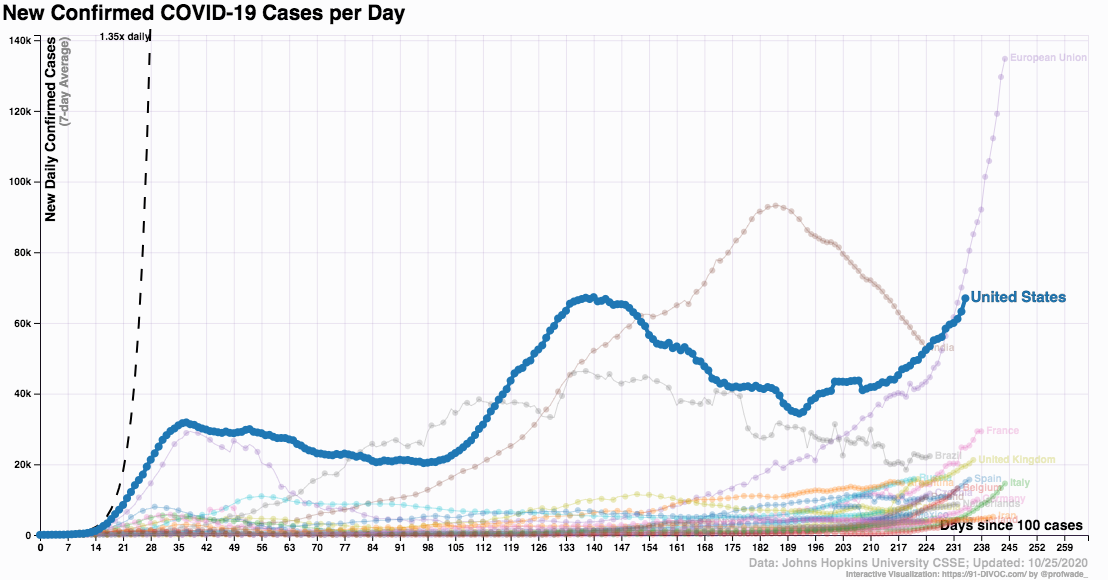

Consider 91-DIVOC data. Infections are definitely rising, now on par with the worst levels America has yet experienced:

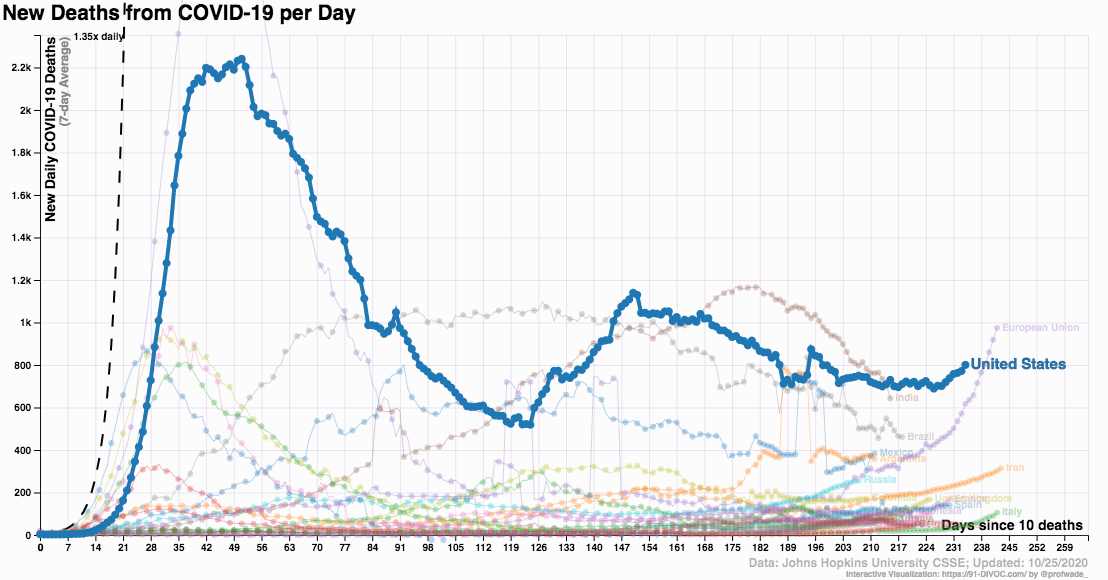

Yet deaths are not rising to that degree. Instead, they are growing slightly, still below recent months’ tolls, and far below the terrible spring outbreak:

Hospitals have improved their ability to treat infected people. So perhaps some see colleges spreading the virus, but that it’s less of a problem than it once was.

Political partisanship Obviously American culture is increasingly divided by party, and the onrushing election is heightening that split. We know that Republicans are much more critical of higher education than are Democrats. Perhaps the latter will maintain their academic support, especially as many fear the GOP is avoiding the science necessary to save the country.

Academic research Universities are, among other things, institutions that conduct vital research for the pandemic. American society might cut us some slack for this, especially if any campus plays a role in offering a successful vaccine.

Geographical displacement Stories of bad outbreaks might occur elsewhere, far beyond our local institutions. If we don’t see horrors nearby, we might set them aside.

Taken together, these views – in favor of campus life and sports, political partisanship, attitudes towards the pandemic, the power of research, localis – might protect academia’s reputation. Or the sentiment that campuses are plague zones, active contributors in making the crisis worse could take hold.

We can test out my theories by checking the next polls of American attitudes towards higher ed.

(thanks to my wife and Jean Potvin)

Bryan – regarding this part:

Our love of the physical campus and disdain for online schooling

My two college-attending but at-home kids are hearing from their friends that they, and their parents, have accepted the risk that being on-campus is worth it, and sure enough, many of them have said they’ve already been infected, quarantined on-campus, and recovered and returned to their routines. They just can’t travel home but they’re okay with it.

I have a feeling this will become an accepted approach this winter and spring. I don’t know what kind of effects this strategy will have on campus communities, and it’s certainly not what I expected, but there it is.

Wow, Ken. It’s worth the risk of infection.

That says a lot.

A deeply thoughtful and empathetic response to the consequences of academic recklessness.

Thank you, Bob. I’m glad the attempt at empathy came across.

Hi Bryan: Just as an anecdote – here in Ann Arbor I belong to a neighborhood social media site. The other day one of my neighbors posted a comment about an incident in which he had to take his wife to a nearby emergency care facility that happened to be located relatively close to where off-campus University of Michigan students live. He said that when he and his wife got there, he started to notice that a group of students were also coming in to get tested for COVID-19 – and most of them were not wearing masks nor social distancing. He decided to leave because he felt, ironically, that he was actually endangering himself and his wife by going to an emergency care facility that happened to also be visited by students who were not being vigilant. I’ve read in the local news that UM is focusing more on off-campus testing – https://www.clickondetroit.com/all-about-ann-arbor/2020/09/25/university-of-michigan-adds-off-campus-testing-to-covid-dashboard-resulting-in-significant-increase-of-cases/ – but not sure how effective that has been. I do know that as a vulnerable older adult, I’ve taken even more precautions since they allowed students to come back to Ann Arbor this fall. We were doing pretty good, but now cases have increased dramatically in Washtenaw county. I feel that the UM president made a huge mistake by allowing students to come back to campus. Why, I ask, could they not have simply kept with fully online at least through this fall and perhaps even next spring? Based on the numbers, it seemed obvious that would have been the smartest most prudent thing to do. Instead they endangered more Ann Arbor residents. It’s shameful, in my opinion, and supports the theory that academia’s reputation is being hurt, and rightfully so in this case.

Holy cats, George: what a story about the local ER. Stay away. 🙁

The motivations for opening look to be clearly about money, at the root.