Today we conclude our reading of Kim Stanley Robinson’s Ministry for the Future.

If you’re new to the book club, welcome! Here’s the introductory post. We started back in November.

With this post we start discussing the fifth and final part of the novel, chapters 89-106 (pp. 445-563). I’ll begin with a summary of the story so far, add comments from readers, add some of my own notes, then ask questions for discussion. At the end I’ll add any resources I’ve come across.

With this post we start discussing the fifth and final part of the novel, chapters 89-106 (pp. 445-563). I’ll begin with a summary of the story so far, add comments from readers, add some of my own notes, then ask questions for discussion. At the end I’ll add any resources I’ve come across.

You can share your thoughts by writing comments at the end of this post. You can also contribute via social media – I’ll copy this post or a link for it to Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, Mastodon, and Medium. I can copy and link to your comments there in next week’s post. You can also respond through a podcast, video, web page… just be sure to let me know somehow.

One more note: if you have any questions for me to ask the author, let me know! I’m sending him the email shortly.

Now, to dig in!

Summary

SPOILERS AHEAD. Obviously:

The climate crisis turns around. CO2 levels drop for the first time, due in part to “greening of the ocean shallows with kelp” (446) but especially to the carbon coin and “drawdown efforts” (455) (chapter 89). More of the economy than ever is tied to blockchains (454-5). The United Nations agree to spread climate pain around globally and more justly (463). The Antarctic has been stabilized (ch 93) and the Arctic Ocean’s albedo reduced (523-4). A new holiday, Gaia Day, is celebrated (546).

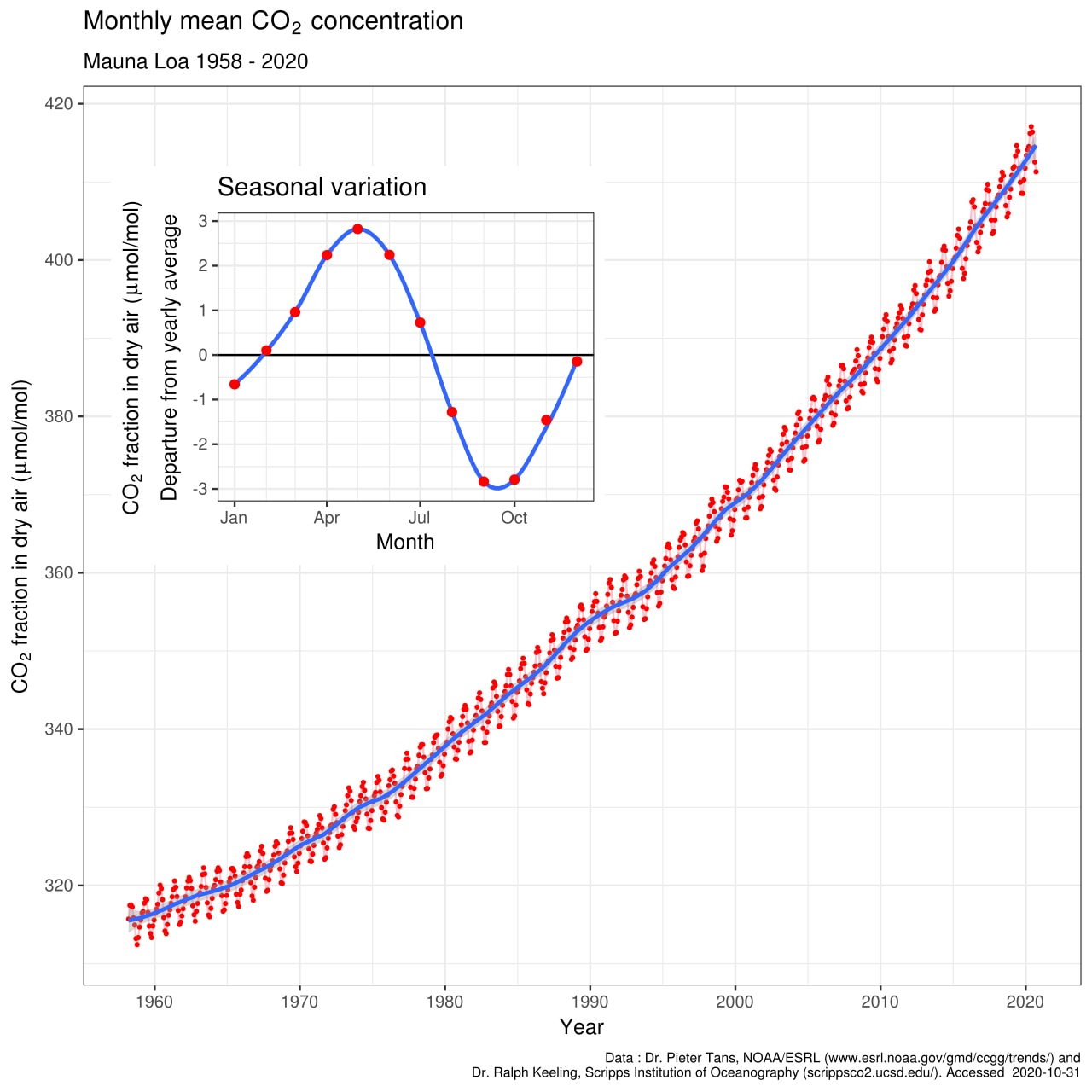

The United Nations Conference of the Parties (COP) meets and shared both good news and problems, including the total human population starting to decline (477, 502), nuclear power and materials, failed states, the status of women, and more (94). They have a poster using the Keeling Curve:

The Keeling Curve (475).

In the Ministry, Tatiana is assassinated (ch 89). Mary retires and Badim succeeds her (ch 98).

Frank has a brain tumor, which kills him. Mary goes on a world voyage and starts a relationship with an airship captain Arthur Nolan.

Notes

From readers:

Joe Murphy was skeptical about terror and geopolitical plots. Joshua Kim and Chris Mayer pondered making climate change central to college and university missions. Lisa Sieverts and Mark discussed the chapter (87) from last week where people relocated voluntarily for climate reasons:

As someone who lives in a small town, I thought it was unrealistic that the Montanans agreed to abandon their town. (Personally, I hope I would do the right thing and agree to leave when it would be so clearly good for the planet.)

and:

I liked what he said about the suburban communities cheerfully leaving their communities. Some developers bought out a small cul de sac near our local college to build apartments and at the time I was outraged that this tiny community had been bulldozed, but now I’m not so sure.

Tom Haymes argues that the novel makes a great case for interdisciplinary thinking and practice.

From me:

The novel continues with more non-main-plot chapters. There is another riddle chapter, the answer for which is not provided (ch 95). There are also meditations on technological determinism (ch 90) and revolutionary politics (ch 99). We get micro-stories about characters we never see again, but who give us glimpses of ideas and the world in transition, like a Hong Kong political activist (ch 101).

Technology: the world uses many technologies and practices we now know to measure the improving climate, “the Great Internet of Things, the Quantified World, the World as Data.” (p 454) An international group tints the Arctic Ocean to reduce its albedo (523-4).

Mary’s new partner is named Arthur, yet he plays no heroic role in the world beyond making her happy. I’m not sure what this means, except perhaps a quiet argument for a world without individual superheroes.

Discussion questions

- What made the successful decarbonization work? How would be describe the strategy?

- Related to 1: which pressure points were squeezed to make the victory happen?

- Some geoengineering plays a key role in the world’s triumph. It’s less ambitious than anything spaceborne, but definitely more than we’re doing (deliberately) now. Is this a kind of geoengineering compromise or middle path?

- Arguably the world’s success was partially driven by terrorism. Nobody is identified as the authors of all of those acts of violence, much less prosecuted for conducting them. In fact Badim, head of the Ministry’s “black wing,” is promoted to the next head of the organization. What argument is the novel ultimately making about the climate crisis and violence?

- What role did higher education play in the novel, overall?

- On the last two pages Mary and Art return to the Ganymede statue (seen earlier) and wonder about its meaning:

“…where the statue of Ganymede stood…. This was a place she often came to; something in the statue, the lake, the Alps far to the south, combined in a way she found stirring, she couldn’t say why.” (34)

Art suggests it’s about a man offering himself as a sacrifice for animals. Is that man Frank? Or is there some much larger sacrifice occurring in the novel?

More resources:

- An apparent ecoterror attack took place in Colorado, breaking natural gas lines.

- What if users owned technology?

- A new Karl Schroeder story offers an interesting take on an environmentally positive blockchain currency.

- The New York Times looks back on the “deep adaptation” paper.

- UPCO2 claims to be “the world’s first tradable, carbon token available on a public blockchain.” More: “When you invest in UPCO2, you invest in sustainably preserving the rainforest, which is good for the planet and your portfolio. UPCO2 is the best way for you to buy, hold, sell or burn carbon credits. It’s convenient, trustworthy and rewarding. It’s a financial incentive to do what’s right for the planet and to do well for yourself in turn. A crypto that’s actually clean.” (thanks to Steve Foerster)

Thanks to so many readers who shared their thoughts so far. Now, over to you for the final round of discussion!

(thanks to Vanessa Vaile, Bill Benzon)

I just finished Ministry for the Future. My reading schedule has been parallel to yours but I’ve avoided commenting until now. I have very mixed feelings toward this work. As a work of speculative fiction I would give it a barely passing grade. Robinson never seems to have the time to tell the story, because he is so intent on explaining the crisis and offering the answers. This will likely turn many readers off. That is unfortunate because we need speculative fiction that helps us understand and confront emotional and intellectually the massive problem of climate chaos. On the other hand, Robinson has assembled one of the most comprehensive collections of detailed climate solution scenarios I have ever encountered. He manages to give due diligence to every possible approach from massive geoengineeering projects to rewilding. For anyone interested in the range of possible solutions the book is a worthy but difficult read. In that sense it is informative if not inspirational. Finally, the one part of the book that leaves me concerned is the rather glib manner he suggests that eco-terrorism is a prime player in causing positive change. He may be right but this is a scary concept to leave out there so unburdened by moral consideration.

Joe, I agree on your last point, and will ask Stan about that.

Thank you for the assessment of the book being too… programmatic? nonfictional?

Bryan, those are both good descriptions. while they are fair critiques of the work as a piece of fiction, I still believe the book has significant value. I see it as a work of scenario or world building. I learned a lot from the reading of it. Because of my interest in the role of story as a tool to inspire positive futures my fear is that the work does not further that goal. It’s a heavy lift and one that few people will likely be willing to carry all the way to the final, anti-climatic pages.

I am so late coming to this discussion, due primarily to a interstate move on my part, but the reading group did push me to buy and read the book. It was somewhere after Week 3’s post went up that I was finally started to catch up with the timeline, and then the holidays were upon us. But enough of my excuses.

Much of the novel I found to be compelling, or at least interesting. The first 25-50% was a major wake up call about what could be coming and possible ways to address the issues and to me seems to the the parts that have generated to most critical calls for politicians and others to read the book. I found the scenarios to be very urgent and frightful in a realistic way. I worry more for my son’s generation and the generation after that if we don’t turn things around, but the book still made me question whether or not there was more that I could be doing in my own life to further reduce my carbon footprint. Having just moved, I know I have far too much stuff and just thinking about the production and eventual disposal of that stuff is concerning.

I found the second half of the novel to be more problematic. Looking at the U.S. today and the recent rise of nationalism and tribalism around the world, I’m not convinced that the world (or particular nations, the U.S. included) would make the decisions required to effect the immediate (10-20 year) changes described in the novel. To your discussion point, it probably would take some kind of violence or subversive action to affect immediate change. The threat of using drones to infect the cattle industry was horrifyingly clever! We’ve seen how little it takes in this country to make so many people question whether the COVID vaccine is safe. Back to the book, I’m not sure how the second half could have been different, but it just felt too utopian, too neat, with a long slide toward Mary’s retirement and Frank’s second death, as it were. Sadly, it felt like an 80s or 90s vision of the future, or even a 70s “I’d like to buy the world a Coke” commercial. Even the whole notion of “carbonies” left me skeptical, both politically and technologically. There are still challenges in the EU and it will be interesting to watch things post-Brexit, and despite the current market highs of Bitcoin, it is still hard to find places where you can use it as a currency. And, have we talked about the environmental impact of producing Bitcoin?

Ok, I’ll wrap up now. For me, the book started out as a very strong speculative fiction, brilliantly employing the global environmental crisis as the incitement to action with a wealth of ideas, but lost the tension about 2/3 in and couldn’t quite figure out what to do with its characters story-wise. (Ex. I feel like I barely knew Tatiana enough to grieve for her.)

Anthony, welcome! I’m in awe of you doing that move, and hope it worked out all right.

Thank you for your analysis of the novel. Your criticism of the second half is powerful.

KSR is very good at launching me on very deep ruminations about the paradigms we accept as “normal.” Ministry for the Future was particularly fertile ground for these explorations. KSR is very good at playing with what Donella Meadows calls “the power to transcend paradigms” as a way of getting to think transformatively about our relationship with our technological existences (http://donellameadows.org/archives/leverage-points-places-to-intervene-in-a-system/).

The challenge is getting our students to think in this manner as a matter of course. This is critical to wide range of societal challenges what will require lots of paradigm surfing going forward. Yet we continue to accept both technological and systemic straightjackets that constrain our thinking and this is a major challenge for education. I explore this in more detail in my latest blog for ShapingEDU at https://shapingedu.asu.edu/blog/technosymbiosis.

If you are interested I will be running a hackathon on paradigm-shifting as teachers on January 6th at 10:45 MST (https://shapingedu.asu.edu/wintergames/January-6).

Tom, I appreciate your focus on interdisciplinarity here.

Good luck with your hackathon!

Reading this some 18 months later, Tom, and struck by the portentious date for your paradigm-shifting hackathon last year! How did it go? Sounds like we may be attempting similar “hacks” with our students, so I’d be interested in hearing more. Feel free to write directly: shautzinger@coloradocollege.edu. Sarah Hautzinger (Anthropology, CO College)

Something else happened on January 6th? 😉

Don’t send this tape to the Committee:

https://youtu.be/yTp_xdyiuk8

It was a good session but no morons in buffalo hats showed up. Just some ski caps. (You’ll have to watch to understand…)

One of the suggestions that Badim makes in the book is that perhaps they should found a new religion dedicated to combatting climate change. I was watching this short documentary last night on the Pastafarians (who have an explicitly pro-environment plank in their gospels) trying to gain official recognition as a religion. It’s an interesting missive on what constitutes religion and what kinds of barriers the kind of “anti-climate change” religion that Bad suggests might face. It’s available on Amazon Prime right now.

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt11134554/

This is kind of an age-old dilemma. Do you reform existing institutions or split off and form new ones. More traditional religions have been interpreted as being explicitly pro-environment although it is just as easy among many to come away with the conclusion that the higher power has granted us the Earth to use as we please. One other possible outcome, besides a shift within existing religions, might be a shift of followers to more explicitly pro-environment religions such as Buddhism.

Look also at what the Satanic Temple is doing in an attempt to thwart laws that are clearly based on Christian fundamentalism’s influence in politics, especially around access to abortion services and, earlier, the installation of Christian monuments on state grounds.

Good points about religions, Anthony and Tom.

Tom, do you think the New Age movement is fertile ground for Badim?

I am not surprised that Badim’s gestures toward a new religion didn’t get very far. It’s hard to start a new religion, especially if you don’t build on existing traditions. Baha’i, which is probably the youngest major world religion, is built on the tenets of Islam. Sikhism is probably the youngest major religion to have no connection to a previous religion, and it draws on elements of various Indian traditions. Successful religions also tend to grow in relationship to a state — either through state establishment or state oppression — and I find it hard to imagine either path working successfully in the world of the 2030s. In addition, nationalism and adherence to existing religions would work against the creation of a new religion that would theoretically gain converts from every other faith.

I also don’t think New Age traditions would be fertile ground for Badim’s religion, because New Age beliefs place so much emphasis on how the individual interprets and practices spiritual truths. It is difficult to imagine New Age adherents agreeing to the dogmas and disciplines that are essential for holding a new religion together.

New Age adherents seem to be especially susceptible to the dogmas of Qanon.

Wicca is a very new religion founded on feminine and earth-based principles. But I don’t see it displacing the patriarchic Abrahamic or Indic faiths any time soon.

Thank you Bryan for this book club — I was on the fence about reading MoF when it first came out but this pushed me over and I was glad I did! Unfortunately, I was pulled away from commenting in earlier weeks, so my thoughts below might include those on earlier sections of the book:

As others have mentioned, I think MoF has great value as a compendium of possible solutions and scenarios, and as a way to get a positive vision of what transformation to an eco-sensible future might look like into the collective imagination. I do worry that the book might not have wide enough uptake to significantly shift our cultural consciousness, but every bit helps, and may reach more audiences than other emerging positive visioning attempts, such as Permaculture Utopia (https://permacultureutopia.com/).

I like that KSR built off of many existing movements, technologies, and structures — e.g. Half Earth coming out of the Y2Y-corridor; Carbon Coin from cryptocurrencies; YouLock from social media; permaculture organizations, regenerative ag, etc, so most of it avoided feeling far-fetched, with the exception of the pebble-mob weapons as leading to an end to large-scale armed conflict. This also highlighted how, yes, we have many of the solutions at our fingertips now, but the problem is the coordination and incentive mechanisms. KSR had the characters tackle this through the central banks and design of a new currency, which may very well be the pressure points needed to bring the changes we need and just might be doable.

Like others, I did find the COP symposium to be the turning point at which I felt disappointed in the book… I found myself wondering “how’d we get here all of a sudden”? That there would be no significant pushback or political unrest, particularly stemming from our dysfunctional information environment, seemed flimsy. But I suppose it’s a balancing act with writing a world-building novel, between how much is included to make it feel realistic and what is left out to advance the narrative without getting bogged down in excessive detail.

The geoengineering presented in the book did seem like a compromise, and the focus on the Artic Ocean albedo reminded me of Jem Bendell’s Deep Adaptation paper (linked to under your “more resources” section above) — targeted/surgical geoengineering to avert the highest risk events. I found it interesting that KSR’s thinking on Antarctic ice-sheets and sea-level rise mitigation seems to have evolved: in the Science in the Capital series they pump seawater onto the icecap, but in MoF this idea is rejected as too energy-intensive. Both stories keep the idea of refilling inland salt-sea basins (less energy-intensive due to elevation differences I suppose).

The terrorism/violence angle is interesting. The Frank character is also a figure of some violence–the initial trauma of the heatwave, his attack on the party-goer, kidnapping Mary, etc. KSR seems to consistently write from the perspective that science, institutions, and technology are the key to a successful future–if only we had the right politicians listening to the right scientists we could turn things around. The book explores the question “how might we use the tools of the industrial growth society to evolve it into something else”? rather than “what would a wholesale collapse and replacement of the industrial growth society look like?” (which would again feel too far-fetched, not be useful as a roadmap, etc.). Violence and coercion are (unfortunately) one of the tools of the industrial growth society. Perhaps the inclusion of terrorism and violence is a further attempt to capture what realistically might emerge from a future of climate chaos? However, that the acts of terrorism provoked no backlash added to my sense the book was straying too far into fantasy.

I wish he would have explored the spiritual / religion aspect further, though perhaps his take was that a shift in economic conditions would give rise to a new religion, and not the other way around. Prior to reading the book, I was worried KSR would be too techno-optimist/carbon-fundamentalist in his approach, so I was happy to see at least some mention of the spiritual, as well as other “life-centered” approaches (rewilding, animal protection, habitat corridors, Gaia day, etc). With the statue of Ganymede, the eagle is on the ground, and the man’s arms are extended in such a way that he almost seems to be saying “let me help you soar again.” Perhaps what has been sacrificed is our human egocentric worldview, allowing enough humility to see that all beings are worthy of our care and attention.

Such mixed feelings about this book, but not because it’s half good and half bad, but because it succeeds and fails SO spectacularly. I find myself disappointed and inspired all at once. I wonder if I’m just not seeing it in its totality; either it’s not very good, or it’s a supreme work of imagination and art. Or both at once. I think part of this is the context of the here and now. We seem to be living amidst such beautiful dreams, and such horrible nightmares (to paraphrase Sagan).

As I’ve written before, I’m responding to this book partly as a leader of a climate change worldbuildling effort called The 2041 Project: Imagining A Positive Climate Future. https://suny.oneonta.edu/science-discovery-center/sdc-online/2041-project

In this context, MoF has been an exhilerating read, a novel of ideas, a novel that attempts–and succeeds–in making monetary policy a hero? We’ve been worldbuilding the America of 2041 for a few years now, and in my head our timeline and KSR’s have merged.

While KSR has largely taken a detour around what I’d call the America Problem (fatalistic and fatally-flawed belief in rugged individualism, a divine-right exceptionalism that innoculates us against learning from others, and a dangerous streak of racism and nihilism and a civic religion that worships the gun), we’ve taken that as our core challenge. We think the world is heading in the right direction, with lots of hollow lip service that will nonetheless spur demands for real change, but the American Problem looms large.

In February of last year, when we ran our first worldbuildling workshop with art and sociology classes, we predicted coming decades marked by pandemics, climate catastrophes like massive wildfires and, most of all, acute civil strife, like Lebanon in the 1980s but dispersed and intermittent, stochastic. And then it was March and major elements of our future timeline were happening all at once. Our timeline’s civil war began with a bombing of the Capitol. We appear to have avoided that on Wednesday, but what did come to pass still shocked many. What’s to come?

We hope we come to unity through dialogue and patient and nonviolent struggle. There’s a lot of theater to American politics, so maybe most of the gun-rattling is just that. But our timeline has us go through the worst, a second Civil War, less bloody but more terrifying than our first.

KSR’s reference to a new religion has been a central part of our timeline for a while. This isn’t prescriptive, but just a guess based on our history. Religion motivates Americans, and we’ve been prolific at manufacturing new religions. Americans who haven’t spent a lot of time out West (in Utah, Nevada and Arizona in particular) are often unaware of uniquely American story of the LDS church–and are often unaware of it’s industriousness and power.

We posited a different origin for the new religion. The Abahamic religions are so bound to a story of dominion over nature. We saw instead the new faith arising out of the nexus between the environmental movement and the movement by and for indigineous rights. Something forged in the crucible of the Standing Rock protests. While the US descends into chaos, the new religion, with echoes of the Ghost Dance and the Longhouse Religion and many other religions but fully centered on Gaia, sweeps the land, especially the Native American reservations, which band together and declare their nuetrality in the civil war. This gives them economic and political power and people–who flee to these Sanctuaries seeking security, opportunity, spiritual connection and community. The Sanctuary Network and the New Gaiaist faith become central to negotiating the end of Civil War Two, in what becomes known as the Black Hills Treaty. In the agreement, the US agrees to give the Black Hills back to the Lakota and the Cheyenne, and agree to set up a process to finally honor the treaties. Electrions are planned and a new Constitutional convention is convened, and the First Nations are included as advisors. The Seventh Generation Rule is written into the new document, as well as protections for gender equality.

The newly-reconstituted United States finally engages in the Green New Deal, a massive effort to rebuild infrastructure (better), and heal the land and the people. A service year is mandated, and new agencies come into being: New Farms Administration, Reforest Service, Refugee Resettlement Agency, Corps of Geoengineers, Great Lakes Water Authority. We start buildling seawalls and carbon scrubbing towers, restoring wetlands and planting trees.

Superimposing KSR’s worldbuildling on our own provides some exciting syncronicities. Half the Earth as a model for rewilding and the work of the new Reforest Service, Carbon Coin as the driver for all these changes, finally a way to put money into the service of the earth. Carbon sequestration through industrial means along with sequestration through preservation and soil rehabilitation. Our service year programs and agencies as the kind of grassroots nitty-gritty projects that some readers wished or expected a Ministry of the Future to oversee.

A main focus of our project is our own institution, and though I haven’t talked a lot about higher ed above it’s our central lens. In our first 2041 podcast, we interview graduating seniors in 2041 who are getting their service year assignments: a hyrdrology student will be working on the Great Eastern Seawall project, a Sustainable Food Systems student will work for the New Farms Administration, helping teaching regenerative agriculture, and a Geoengineering student whose brother was a wilderness firefighter will be replanting forests for the Reforest Service.

I think I understand the way KSR ends MoF because it’s a key part of our 2041 project. We need a positive vision for the future that isn’t escapist or unrealistic. Bad stuff will happen. Things will get difficult. There will be conflict, struggle and failures. We’ll have to change, and that’s hard. But we need to see ourselves on the other side of that, and envision how that might actually be good for us. Can we live happier lives with less stuff and more community? Less work, more music. Can we replace consumerism with connection and creativity? Mary and Arthur’s walk through Fastnacht in Zurich is our chance to imagine that. We can survive, and we can rebuild and transform and create something better.

KSR has attempted to answer some of the stickier questions that plague this kind of work. How to rectify our aspirations for the future with the realities of capitalism and money? How do we transform banking and capitalism is the surface question, but the underlying human question is how do we change our relationship to the earth and its living systems? And can we find a new kind of humanism in that future?

Note: my favorite part of MoF were the airships. I just love airships. Bring on the airships!

Doug,

Wow, impressive work you’re doing there. I keep wondering (hoping) that this week will mark a tipping point in peoples’ realization of the pathways that they are being led down. As a teacher trying to explain politics and government in deep red Texas (my Congressman is one of the ones who challenged the election results in the House), trying to help my students, who are largely from disenfranchised parts of society, care and understand how they fit into all of this is a monumental challenge. Some of them are interested in climate change and I will refer them to your site. I remain optimistic but the clock is definitely ticking on all of us. Thanks for your work.

Thanks for your kind words Tom! I appreciate the challenge you are facing, too. If you have any suggestions for 2041, let us know. And if you want to replicate/adapt it or any of its parts, we haven’t stated so but we consider it to be in the creative commons.

Sorry for chiming in late. The reminder email for the final week went into a spam folder.

Like several who have already commented, I was ultimately disappointed by The Ministry for the Future. I admire KSR’s ambition in writing a work of fiction that is both descriptive and didactic, about one of the great societal challenges of our time. His deftness as a storyteller in weaving diverse fragments into a narrative was also on display. Yet I kept feeling that there was something missing.

In pondering what that was, I came up with two primary answers.

First, this was a book in which everything changes, and yet nothing happens. It’s the story of the world decisively stepping away from the climate abyss and materially changing the direction of global civilization. And yet, there’s virtually no story. It feels like Mary and Frank and Badim hardly do anything, as far as we learn in the book. There are points where the characters’ awareness changes, but no particular point where the world changes.

This is probably an accurate representation of how we tackle climate change, if we do. The big problem all along has been the disconnect between individual experiences (of people and corporations) at a moment in time, and the collective effects for the planet over long time-scales. We don’t do enough, even when we see the science, because the effects feel diffuse and far off. So on the other side, when we actually do start doing enough, it will probably look similar. “Inflection point” is one of the terms that is throw around too much in Silicon Valley without much thought. It’s a mathematical concept of when a curve changes direction, perhaps subtly, not necessarily a sharp break that’s obvious to all. The book constructs a scenario for inflection points in bending and ultimately reversing the curve for climate change. But as a reader, one looks in vain for clear lessons, heroes (as I pointed out in an earlier comment), decisive victories, and transformative moments.

My second conclusion is more clearly a criticism. Ministry for the Future is a book about institutions, which doesn’t understand them. KSR realizes, per the prior point, that heroic individuals don’t transform history through force of personal will. How do you tell a story about grand geopolitical events? Some guy named Tolstoy did a pretty good job in a book called War and Peace, so it’s possible, but challenging. KSR has the additional challenge that, in the contemporary world, individual actions are mediated through institutions and organiations. So he frames the book around them — primarily the Ministry and central banks, but also decentralized ones like the Children of Kali.

The trouble is that we never see any kind of realistic picture of these institutions. The Ministry supposedly has a $60 billion annual budget, yet it’s basically five or six people who meet and decide the future of the world based on their own personal analysis. There’s no staff except for the note-taker inserted as a narrative device. Where are the meetings divisions and offices and reports and so forth? Same with the central bankers — the scenes are written like they are the Illuminati. While there are times when leaders do get together in a room and make critical emergency decisions (e.g. during the financial crisis of 2008), even then, there is more surrounding activity, and that’s the extraordinary cases of emergencies forcing either/or decisions, which are (per above) the kind of sharp turning points the book wisely rejects.

Bureaucracies do change the world. They have done so many times, and there has been brilliant analysis (e.g. Max Weber) on how they do. We’ll need them to do so in order to confront the climate emergency. Unfortunately, KSR doesn’t try to tell that kind of story. He also introduces but doesn’t attempt to examine the decentralized alternatives structures for collective action, in the form of the Children of Kali. Again, we know they’re out there, but we don’t see them except for one meeting Frank has early in the book. And as I’ve written in earlier posts, the technical mechanisms built on cryptocurrency and privacy pods are based on the right technologies, but described more as magic than realistic systems.

This last point matters for the final reason I found the book disappointing. As Cory Doctorow noted in his review, Ministry for the Future is in some ways a book about the end of capitalism. And yet, the alternative presented is a kind of hypercapitalism, based on a cryptocurrency (Carbon Coin) creating an economic incentive for companies and countries to do the right thing. There is a great deal of potential in using cryptocurrencies and decentralized autonomous organizations to align incentive structures in new ways. But there are also tremendous dangers that these systems recreate the old concentrations of power, with fewer democratic protections. In KSR’s story, the bankers get richer, and the Saudis (minus the Saud family itself) get richer, one individual heading a UN agency makes crucial decisions for the global economy, and we’re supposed to imagine this is part of a dispersion of power and wealth away from our current environment of inequality.

We briefly see one example of some farmers who are empowered by the new system, but again, it rests on a massive global implementation army that somehow just happens. Why aren’t the agents responsible for paying the farmers as corrupt as such agents often are in the developing world today? That’s the hard part, on the ground. It always has been. It always will be. And to close, if we want to project from the book to the context of education, it’s the same challenge there. Institutional change is hard.

Even though I didn’t enjoy the book as much as expected, I appreciate Bryan bringing us together, and everyone else who commented. Hoping to have time to join another one of these book clubs in the future.

I tried to answer Question 1 the way that a historian would answer in 2068 or so.

<>

Without intending it, I think I answered Questions 2, 3, and 4 too. And I think I’ve spent quite enough language on Question 5 in my tardy reply to Part 4.

So on to Question 6. I think the explanation offered by “Art” (is this another example of KSR’s on-the-nose names?), only gets about halfway there. In the myth of Ganymede, Zeus was so drawn by Ganymede’s beauty that he carried Ganymede away and granted him immortality so that Ganymede could live forever as the cupbearer to the gods (or to Zeus himself depending on the myth). It’s not just that a human offers himself as a sacrifice for the animals, but that the gods reward those who are beautiful – or, stretching it perhaps, those who protect the natural beauty of the earth. Mary, and perhaps Frank, and Tatiana and Pete Griffen and all the Indians who died in the heatwave, will be rewarded in heaven.

Then again, Mary herself implies there is no meaning, no reward, that the only thing is to go on.

Incidentally, I don’t much care for Mary’s relationship with Art. This is not a typical romantic-comedy situation, where we can see the lovers are right for each other and are united only after overcoming the obstacles of the story. As I mentioned in a late comment on Part 4, people who work on big projects tend to sacrifice happy families and relationships. Thus Mary keeps company with Art only after she retires. So it’s not all that satisfying when she opens herself to a relationship this late, to a character we don’t know that well. I think that KSR’s choice to cover so much ground in the novel costs us the emotional attachments that we can form in some of his other works. And perhaps that explains some of our collective restlessness with this story.

Still, I’m glad KSR created this mountain for us to climb; even if we don’t get to the top, it’s still satisfying to make the attempt.

Thanks to all for their readings, and to Bryan for hosting. On to the next!

Whoops. It seems my clever device of putting my “historian’s text” in angle brackets was read differently by the software. Here’s my text.

Decarbonization happened because of a lot of things. The India heat wave was a public wake-up call that says, this isn’t a problem for the future but a problem of right now. Terrorist acts followed, for years, which showed another kind of cost of climate change; people will respond with terrorism when it is the best available option to them, so we really ought to give them better options. The emergence of YourLock (aside: I think this is the least probable aspect of the story) and the student debt strike showed that actions by individuals can have a collective impact. None of the personal gestures so frequently advocated in the first two decades of the 21st century — increased recycling, adoption of cars that run on electricity or biofuel, the replacement of plastic bags with paper ones – could ever have more than a negligible impact on carbon use. But the efforts to replenish the Antarctic ice cap and restore habitats for wildlife represented the ways that scientific efforts contributed to the change – nothing magical like figuring out how to dissipate carbon into space, but a workable project that achieves a significant goal within the larger project. The “Pinatubo bombings,” and the early resistance of the central bankers to the carbon coin, demonstrated that individual nations will do what they want to do when it suits them. But the adoption of the carbon coin, and its early embrace by oil-rich but smaller economies like Arabia and the various African countries, represented both the piecemeal way that solutions happen as well as the need to find economic carrots to incentivize carbon reduction (and not just economic sticks like cap-and-trade or carbon tax). Carbon coin adoption also represents the way that governments (and I include the Ministry in that group) used events and historical circumstances to advance their plans – but that was possible only when they already had good plans in place, so that when the iron is hot they could strike.

Pingback: When “hope and history rhyme”

The Ministry for the Future is also about looking back. It’s about learning from the past, paying respect to those who came before us, and remembering the sacrifices they made so we can continue to build a better tomorrow. https://framedgame.io

And finally, the Ministry for the Future is also about dreaming big and aiming high. It’s about believing that anything is possible and setting our sights on the stars.

Pingback: Technosymbiosis – IdeaSpaces