My son and I watched Alien: Covenant today. We were the only ones in the theater, so Owain and I could indulge in our bad habit of talking while a movie plays.

Here I’ll continue my infrequent practice of blogging movie commentary. After the next paragraph, please assume massive spoilerizing.

Here I’ll continue my infrequent practice of blogging movie commentary. After the next paragraph, please assume massive spoilerizing.

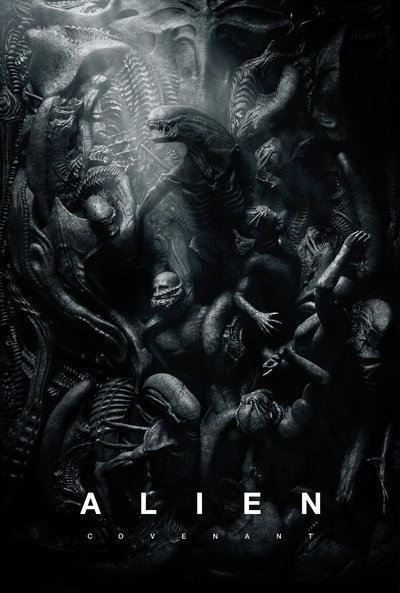

First off, general reactions: this film is good, if not great. It’s very good for Hollywood-funded fanfiction, if I might be so harsh. Some gorgeous visuals, Michael Fassbender having fun, several good references and call-outs (from Blade Runner to Wagner), some humor, one bit of sarcasm in the ending, several great action scenes, and people acting less stupidly than in Prometheus (2012) are positive points. It’s definitely better than Prometheus. The English prof in me enjoyed a plot point about correct citation of Romantic poets. Fans may enjoy numerous callbacks to the original movies.

On the negative side, there’s weirdly old technology (see below), underdeveloped characters (one stands out because he has a hat), some small but potentially useful plot threads dropped, and the ending.

It’s not in the same category as the classics, Alien and Aliens. Yet it’s well worth seeing on the big screen.

Second, ah, let me give this its own header.

Retro technology

A few months ago I wrote about how another big Hollywood science fiction movie carefully restrained future technology to a specific threshold in the past. That was Rogue One, and it strove to keep advances to the 1940s, achieving something like dieselpunk cinema. Alien:Covenant does something similar, and for related reasons. The technology never leaves the 1970s, and that seems to be quite intentional. I wonder just how widespread this retro tech meme is becoming in contemporary film.

Yes, there is a starship, and advanced space shuttles, and androids. I grant you all of that. But their roles are understated, their functions unfuturistic, and overshadowed by the absence of technology after roughly 1980 – or 1979, when the very great Alien was released.

There is no internet in Covenant. People communicate largely by radio, or observe each other (very crucial to the film; consider the opening image) over closed-circuit tv. Some members of the expedition record themselves on video, a la the marines in Aliens (1986), but the videos never appear again. Nobody blogs about their experience or shares a selfie on Instagram, neither for themselves nor for the historical record – and do recall this is a colony mission, so perhaps the eventual settlers would appreciate media from the long trip. There isn’t a ship Slack channel.

We could explain this by noting that interstellar space seems to break up internet connections, as the final dialogue lines refer to a one-way, much delayed transmission. Even if we grant that, none of the characters use any technology socially or personally. There’s no sign of quantum computing. Nobody checks for news from Earth or other colonies after they wake up from suspended animation. It’s an isolated, pre-internet environment.

Human-computer interaction is largely via keyboard and screens. Only Mother can be used by speech, and she’s nowhere near Siri levels, addressable only by simple commands. Gestures don’t control anything.

Things get worse in David’s necropolitan world. He uses no digital technology to speak of, despite having access to the old alien ship’s holograms. Instead he builds a flute (out of what, hm?), uses an old microscope, and draws by hand on paper he apparently made himself, then stores as scrolls in cubbyholes. Forget 1980; if David wants to take evolution forward, he certainly is comfortably flinging media technology far back into the past.

Also missing is any sense of robotics, beyond the two androids (yet see below). The ground crew doesn’t send UGVs ahead into dangerous situations, despite having an only-shown-once bot. Instead, they hurl themselves into dark corridors and down scary holes. Even the ship’s computer, named Mother in homage to the first film, is not very bright. There aren’t even any satellites, the positioning of which would have helped the planet-to-orbit communication problem.

Armed people advancing through grass. It could be 1968.

Medical technology is similarly retro. Unlike Prometheus, which featured an ambitious autodoc familiar to science fiction readers, Covenant‘s med tech is smack dab in the 20th century. Injured and sick people receive gauze patches, bandages, and (morphine?) shots. Nobody takes a benevolent dose of nanobots, say, or enjoys a Star Trek medbay. Nobody seems to live longer than they do now, too. And nobody backs up their consciousness online.

There’s very little use of data or data analytics. One crew member accidentally picks up a radio transmission, which the team plays back… and does nothing with. They don’t clean it up, despite the file being in terrible shape. One person hears it and the sound reminds him of a song. We never see analysis of the planet’s atmosphere (my son generously assumed they’d done it). Nobody maps the necropolis or tries to model the medical horror that strikes two spore-infected crew members. It’s a low-data situation.

The starship actually matters little as a vessel for interstellar travel. Within and without, it’s basically 1980. Crew members use bulky spacesuits with jet packs and radio, not (say) nanomolecular suits or force fields. The powerful engines that drive the ship across the vast gulfs of interstellar space aren’t used to (say) toast the necropolis. We don’t see antigravity devices, teleportation, time travel, energy weapons, or any of the tools we imagine for the future. The starship is basically a railroad carriage or 747.

There are androids, but they are as digital as golems. After a quick opening sketch they present as quirky humans, unsusceptible to logical tricks or software hacks. Cut, they barely bleed, not even like sperm-fountaining Ash in the first movie. They never expose circuits. David and Walter are, in effect, magical beings. Like Frankenstein’s monster, we learn precious little of their creation. Their technological aspect ultimately matters little. David’s actual desires are about biology and horror, not machinery.

The textures of Covenant‘s world are very 1980. There are a good number of switches and low-res screens. Characters stomp through an alien landscape packing shotguns and plastic-wrapped video recorder supports, sporting coats and caps. Doors are heavy and strong, capable of wounding limbs caught in them. Vehicles include trucks and crane-lifters. A biologist uses old-fashioned syringes and bottles to take and store water samples.

One character reminisces about wanting to build a cabin out of wood, and uses an old iron nail as both memento and weapon. A shower room is gated off by vertical strips of plastic. Covenant feels very tangible in a way comfortable to someone living during the Carter or Reagan administrations.

Why do this? Why evoke a future capable of technological innovation only to ratchet things back to the Cold War?

I think that Covenant is like Rogue One in that it wants to be a work of historical fiction. It’s trying very hard to evoke the original movie’s feeling and themes. The starship offers many echoes, from digital signage to the dipping bird, sleeping bods (barely altered), and increasingly claustrophobic hallways. The ship and some of the ground action also echo the second film: a planetary drop/personnel stress test, a problematic leader, big industrial equipment used to bash critters. Scott is taking us back to the late 1970s and early 1980s, and won’t let subsequent or more futuristic tech get in the way.

Does this historical location reference period films? To a degree. There isn’t anything like the Cold War (indeed, there aren’t any politics, beyond a too-quick discussion of religious belief as disabling for career advancement), but there’s a post-Vietnam sense of uncertainty about ambitious plans. Perhaps people who lived through that era will feel an extra sense of dread, translating (maybe) the threat of thermonuclear war into fear of aliens. Perhaps.

Maybe a better explanation is that the lack of advanced communication technology isolates our protagonists. Not having information or allies definitely ramps up stress levels. Being alone on a far-off world enhances the emotional pull of isolation.

Above all, the retro tech sets up a horror film.

About the horror aspect –

More space Gothic

Alien: Covenant is, generically, a work of Gothic horror, like the original film. Alien was, famously, a haunted house in space. Covenant moves from deep space to a planet’s surface in order to dwell within a haunted city.

One version of Arnold Böcklin’s “Isle of the Dead”, nicely recreated about 60% of the way into Covenant.

By Arnold Böcklin – 0wFgMTIQ3kZCpg at Google Cultural Institute, zoom level maximum, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13251755

Covenant uses so many classic tropes, beyond the obvious death, gore, and decay. Hidden truth lurks in a basement (David’s eggs). There’s a fun doppelganger with the two robots. The second setting of the film, after the starship, is “a damned necropolis”, in David’s words. It’s an enormous city of the dead (corpses visible right from the start) complete with vast architecture, ominous and huge faces, and plenty of darkness.

As Matt Seitz puts it on the Roger Ebert review site,

The atmosphere inside David’s city of the dead encourages that sort of engagement. It’s one of the great sets in horror movie history, right up there with the refinery vessel in the first film and the infested colony in the second. The medieval look of the place (it seems to have been carved from volcanic rock by laser) drives home that “Covenant” only looks like a hard sci-fi film about technology and rational thought. [emphasis in original]

Also on the Gothic horror register: a nude sex scene interrupted coyly by xenomorph, which is a two-fer: a slasher film cliche and a Gothic trope (deviant sexuality). Bodies are frequently invaded and corrupted. There is what amounts to a truly terrifying live burial.

The great Gothic novel Frankenstein is in play from the opening scene, when a magnate awakens his android creation. The theme returns when David takes the stage as an isolated character, and is gradually revealed to be making life. His doppel-logues with Walter ultimately turn on the ethics and ontology of artificial life. What is humanity’s responsibility to its creations, and vice versa? Are the created entities to serve or replace their creators? Think, for example, of Victor Frankenstein’s thoughts when confronted with the specter of his monster reproducing with a bride or mate:

a race of devils would be propagated upon the earth who might make the very existence of the species of man a condition precarious and full of terror.

The film ultimately takes the monster’s side, as David disguised as Walter “buries” the two human survivors, disgorges and safely stashes two xenomorph embryos as a nice Noah’s ark joke, then contemplates the epic possibilities of biological havoc he can wreck upon the still-sleeping colonists. Scott hilariously scores this terrifying scene to Wagner’s “Entrance of the Gods into Valhalla“, making the dark triumph also a bit sarcastic. That use of Das Rheingold also offers a potential silver lining, in that the gods/David’s triumph contains the seeds of their eventual and utter destruction.

This ironic juxtaposition of horror with soaring music reminds me of the end of Herzog’s Nosferatu (1979), where the titular vampire escapes a trap to heroically ride off into the sunset.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OTDSkCxkPzw]

How does technology play in to the Gothic horror dimension? There’s a hoary tradition of presenting technology as an object of horror (cf this one disturbingly long-running blog project of mine), but that’s not what Covenant is about. Instead, it uses technology to isolate people, reducing their power and making them frightened. Which is what movies have been doing with cell phones since 2000:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XIZVcRccCx0]

In this movie spacecraft isolate and strand people. Technology fails to connect, as radio signals fail and nobody actually uses video footage. There’s no way to learn about anything except through talking to unreliable people and checking out their disturbing drawings. The monsters are stronger than technology anyway.

Covenant is ultimately about the fearsome failure of technology. Perhaps the real meaning of the title is the breaking of an agreement between people and the digital world. We contribute our faith, money, time, and attention to technology and it agrees to entertain and empower us. When the digital world abandons us, dropping us in 1979, we are nearly disabled and quite terrified, offline in a city of the dead – and, far worse, the living.

Bryan, perhaps you could coin a term for “fear of loss of internet.” Provided there isn’t a good one for that, yet. 😉

Thing is, the technology has a retro look because Alien: Covenant and Prometheus are prequels to Alien and take place about 20 and 30 years respectively before that film. The technology has to appear more dated. The internet was barely 5 years old in 1979 and not widely known.